By David Apgar

U.S. war policy against the Islamic State (IS) has it backwards. Roughly speaking, the goal of the United States is trying to eradicate the jihadist group in Iraq with ground support from the Iraqi army, while merely seeking to contain it in Syria with pinprick bombing missions.

This is a calamitous choice: Only the opposite might have a prayer of success – containing IS in northern Iraq, while trying to eradicate it in Syria.

Rethinking the U.S. Strategy Against IS in Syria: Why the U.S. government should use mercenaries in Syria.

The current strategy unfortunately misplaces causes and effects of the problem geographically. The rise of the current insurgency uses the Syrian disorder and eastern power vacuum to establish a temporary launch pad, but Iraq has always been its home and main target.

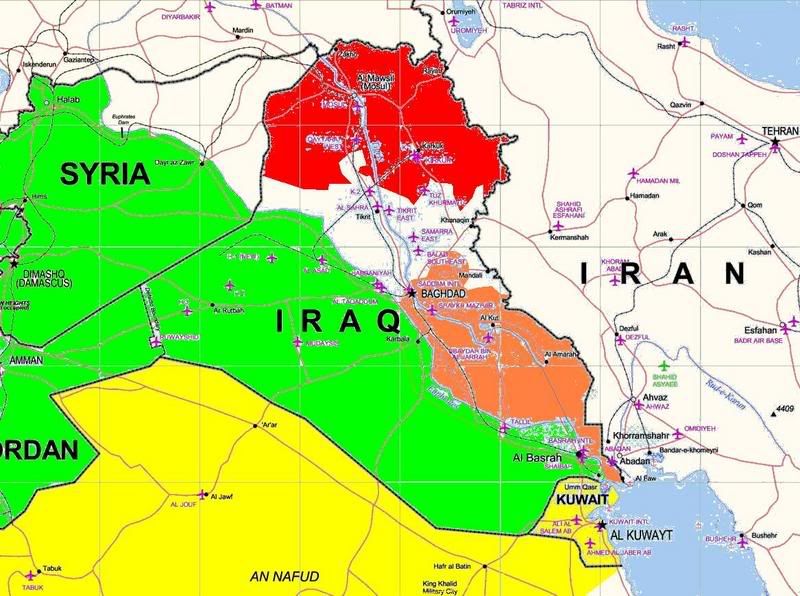

While Syria offered a convenient staging area, Shia-dominated Iraqi politics was the motive, and the goal of the Sunni primitivists of IS was to regain control of the latter country’s Sunni north and West.

The membership and commanders skew far more Iraqi than Syrian, and the bulk of the campaigns have been eastward toward Baghdad or Mosul, not westward toward Damascus or Aleppo.

Although few would dispute the merits of this strategy – Iraqi containment, Syrian eradication – it is controversial. One would need to sacrifice not just one, but two sacred cows of U.S. politics in the region in order to implement it.

The first sacred cow is the integrity of Iraq. The second – discussed in the second part of this article – is the longstanding U.S. reluctance to recruit mercenaries.

Sacred cows and U.S. strategic goals

Here’s why those sacred cows are really oxen that ought to be gored – and why there might be a path to success against IS.

Regarding the first sacred cow – the integrity of Iraq – there has long been an argument for splitting Iraq into two. (I first made it in early 2007, during the Iraq War:Part I and Part II.)

The argument still holds: The conservative Shia of the south suffered too many atrocities under Saddam and had to renounce too many religious traditions under secular rule to be expected to embrace Saddam’s Sunni friends and family as brothers in government today.

That implies splitting the country’s Sunni north from its Shiite south. And it suggests trying to contain IS within the river valleys above Baghdad, the old Sunni heartland.

During the Iraq war, there was a case for keeping modern Baghdad with the secular, Baathist north and drawing a new, internal east-west border south of the city. Today, Baghdad must be protected from the depravity of IS, so the new border must run north of it – keeping the violent extremists out of the city.

Some might argue that the inclusion of the city in the Shiite half of a partition of Iraq somehow hands the city to Iran. In fact, it merely confirms the status quo today, since the Shiite government has refused to share power with Sunnis.

Moreover, Iraq’s Shia are not necessarily as close with Iran as one might assume. And however sectarian that government has proved to be, it at least has not been severing heads.

The split has five advantages:

First, it limits IS to the four or five hometowns of the experienced and capable generals who once served Saddam – and now serve IS – and ends the recruitment tool of Shiite governance over Iraqi Sunnis. This also makes sense because capable and experienced generals will never give up their home turf and will probably never be beaten on it.

Second, it reasserts a forceful Sunni counterweight to Iran within a few hours of the border. The overthrow of Saddam turned Iran into an unchallenged regional superpower in one of the most stunning U.S. strategic errors in recent history.

Reviving a strong Sunni state and military will put enough pressure on Iran to allow its moderate (pro-cooperation) faction to reassert itself over the go-it-alone hardliners.

Iran’s moderates have always been more successful at working with the wider world – including with moderate Israeli governments.

Third, it frees the Kurds to govern themselves, since Baghdad would no longer exercise any claim to the Kurdish northeast. Long sought by the Kurds, Kurdish self-government offers something for everyone. The Shia in the south could care less. The Sunnis under IS will never defeat them in their mountain strongholds and will have to learn to live next to them.

Moreover, nothing would prevent the Kurds from resuming a federation with the Sunnis north of Baghdad if they overthrow IS. With Kurdistan now in control of many of the key oilfields in northern Iraq, non-extreme Sunnis have an economic incentive to patch things up with Kurds after an IS collapse.

And no one should indulge Turkey’s old complaint that an independent Kurdish state on its border poses a threat. For one thing, Turkey could dissipate that threat by simply treating its own Kurdish population with more decency.

For another, Turkey lately embraced the Iraqi Kurds – with weapons, money, and words of support for Iraqi Kurdish independence – as a Machiavellian counterbalance to their own Kurdish separatists. It would be insincere to complain now.

Fourth, splitting Iraq into two leaves a mostly homogeneous state to the south that craves conservative religious rule and could finally obtain it without having to impose it on any large dissenting minorities.

Shia Southern Iraq and Baghdad would be stable, rich, and large enough to serve as a bulwark against Sunni extremism in the Mesopotamian desert. (How the world changes: Given the IS peril, the Iran-friendly Shia south becomes a de facto strategic partner of the United States.)

Fifth, the new southern state would control only half the oil that Iraq controlled. That is plenty for its 15 million inhabitants, but not so much as to exercise the disproportionate control over oil markets Iraq once enjoyed.

In sum, the United States should reverse itself, focusing on containment of IS forces in the parts of Iraq where many of them were born. The resulting partition of Iraq will stabilize the region by reducing conflict within the country’s old borders and providing a counterweight to Iran. That leaves the question of what to do in Syria for the second half of this article.

Editor’s note: Bill Humphrey provided analytical inputs for this article that the author would like to acknowledge.

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense