Good governance is imperative for successful private sector operations. Stable, predictable, and efficient business operations relyon a strong enabling environment with predictable rules and practices. How to ensure that such conducive conditions continue was the subject of a pair of roundtables hosted in July at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. These roundtables, conducted under the Chatham House Rule of non-attribution, included representatives from civil society, the private sector, and government.

The connection between good governance and business operations is intuitive. Corruption hampers business practice both in its attack on market-driven forces and in its unpredictability, wherein a corrupt actor can regularly return with new rules and new demands. Forced labor is not only a normative scourge, but also artificially lowers prices by forcing companies that pay workers in their supply chains to compete against those that do not. Environments without labor rights lead to horrific situations where individuals are exploited, killed, or maimed, but also destroy predictability by creating high worker turnover. These realities are in addition to the baseline governance that is required to maintain roads, electrical supplies, ports, healthcare for workers and managers, and countless other elements of business operations and workforce continuity.

This connection between governance and commercial viability illustrates a fundamental gap in the current U.S. approach to commercial diplomacy in the developing world. While diplomatic efforts to open new markets for U.S. industry have been a part of U.S. foreign policy since there has been a United States, modern efforts have consistently been paired with development efforts focused on good governance. In this way, while embassies may work with U.S. companies to heighten their investment opportunities in countries, other efforts would run in parallel, working to combat corruption and improve governance in those countries.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo

Take, for example, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). While the DRC has long been a target of foreign direct investment from the United States and elsewhere due to its vast mineral wealth, it has suffered from poor governance since before independence. This led to U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) programming aimed at countering corruption, in particular in the mining sector, and efforts to publish and equitably distribute mining revenues to mining areas to reduce grievances, leading to greater social cohesion and improving peace and security outcomes. U.S. development funding also worked with organizations protecting whistleblowers and prioritized independent media to ensure that violations came to light, further improving the business atmosphere.

The dismantling of USAID and the reorganization of the State Department impacted all development sectors, but democracy, rights, and governance (DRG) work was among the most impacted. This means that much of the work that supported an enabling environment for business and investment is no longer funded and has had to cease.

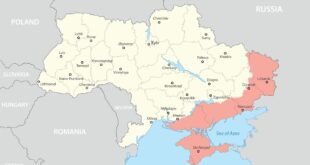

The termination of grants and contracts supporting the enabling environment does not, however, terminate business interest in operating in these spaces. The mineral wealth of the eastern DRC makes it a major target of foreign direct investment (FDI) and economic development efforts from both U.S.-based and international companies. This is particularly true given the peace deal inked between Rwanda and the DRC and the focus on mutual economic development and the mining of critical minerals. Such continued and intensified focus begs the question: How can the work continue and scale if there are going to be sharp decreases in the quality of governance, with corresponding increases in corruption and similar business impediments?

Who Can Do What?

FDI has long been a centerpiece of countries’ development strategies. In addition to the economic development and job creation that comes in through foreign corporations setting up shop, there are often corresponding development contributions, such as the building of infrastructure like roads and ports, as well as hospitals and schools. These development contributions are both elements of public relations and corporate largesse as well as a practical part of conducting business. Without functional infrastructure, operations are slowed or products cannot make it to markets in an efficient, cost-effective manner. Without baseline care and education facilities, workers cannot continue their roles, and it is impossible to attract talent.

This pragmatic approach must deepen in the wake of U.S. retrenchment from foreign assistance. In addition to the traditional development efforts detailed above, companies investing in countries must increasingly contribute to improving governance to ensure continued and predictable operations. There are no longer parallel operations that will ensure these improvements take place.

This will likely be an uncomfortable role for many corporations. While building roads and infrastructure are well within the competency of companies looking to build mines, efforts to strengthen the connections between civil society and local government may be new to them. Building and staffing hospitals are complex, but a part of the history of FDI, while building out inclusive and sustainable dialogue may not be. For this reason, it is important that early in this new era the private sector works with international civil society and governments to determine what is within their capabilities and bring on people that are equipped to conduct this work.

Part of this determination involves assessing what is outside the realm of the possible. Corporations owe a duty of care to their shareholders that requires that profit-seeking be a centerpiece of corporate decisionmaking. That means that efforts that risk having operations canceled are likely a nonstarter. In the recent CSIS roundtables on this topic, an individual who has worked in both human rights and anticorruption for many years in a now-previous role with the U.S. government stated that they never had a more forward-leaning human rights audience in foreign governments than when they attempted to discuss efforts to counter corruption. In other words, even normally sensitive conversations on human rights were deeply preferrable to those aimed at countering corruption, which in many contexts are a political third rail. The latter also inevitably includes work to support those on the ground aiming to counter corruption, such as support for independent and investigative journalists and whistleblowers. This type of work is unlikely to ever be within the reasonable remit of the private sector.

Of course, this leaves in the work that is, as yet, unfilled. The private sector is well equipped to convey these gaps to the federal government after a thorough and detail-oriented examination of what companies can do in the space. Industry understands the importance of good governance in the continuity of operations. A thorough examination of what types of governance work is possible, while maintaining business access allows for a candid discussion with government interlocutors about what the U.S. government must do, in particular in an era where commercial diplomacy is prioritized.

Recommendations

1. Work with trusted on-the-ground partners to understand the local political economy.

The cancellation of USAID and State Department grants and contracts has left an abundance of previously vetted organizations in target communities with immense skills in conducting good governance work. Further, the significant layoffs at USAID and at the State Department have created a glut of skilled and dedicated individuals with the capabilities to manage and facilitate those relationships and that work.

These partnerships are invaluable in determining the needs of communities where investments are planned. A lack of such consultation can lead to a misunderstanding of local grievances or group dynamics that can foster resentment and eventually threaten stability, which can lead to stoppages in operations. It is impossible to reach the levels of granularity required for operating in complex environments without local partners and trusted interlocutors.

2. Develop headquarters-level multistakeholder communities of practice around good governance and business operations.

In order to understand which efforts fall within the reasonable remits of various stakeholders, the private sector should develop multistakeholder communities of practice, operating based on sector and/or geography. This would entail representatives of the private sector, civil society, and government discussing governance and capabilities in a regular and ongoing manner. These groups can both be utilized for frank conversation and collaboration and can serve to harmonize and align efforts, all of which were identified as major gaps in the recent roundtables.

These communities can be used to develop trust between actors to incentivize rather than punish incremental progress, which is both a trademark of good governance efforts and can be a target of those who would prefer to see grander efforts. This trust is deeply valuable for all parties. From a corporate public relations standpoint, companies are more likely be lauded for good efforts than attacked for not going far enough. Civil society organizations are more able to play a role in the design and prioritization of efforts while having their concerns heard and responded to in a private setting.

Finally, such communities of practice could serve as vital fora for U.S. government representatives to hear from the private sector and civil society about remaining gaps that lie beyond their capabilities or reasonable responsibilities—gaps that, if they are to be filled, must be filled by the U.S. government.

Andrew Friedman is a senior fellow in the Human Rights Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense