Nourinne Akhtar

The idea of democracy has been more than a political system over centuries; from Plato’s Republic to the rise of twenty-first-century populism, it has been a moral aspiration, a promise of collective self-rule based on justice, equality, and human dignity. And today, that moral core seems to be badly fractured. Not only institutional decay but a deeper ethical crisis is ahead for democracies around the world. Public trust is eroding, civic virtues are collapsing, and the very concept of a common good is being dissolved under the pressure of populist rhetoric and hyper-individualism. This was not an overnight crisis. Its roots go back to the tensions Plato identified in the decay of democracy into tyranny by popular will if virtue and wisdom are not cultivated.

It’s not just that we have demagogues or misinformation; it’s that democratic ideals have been hollowed out from within. Foucault’s idea of ‘governmentality,’ the ways in which modern power works indirectly through the formation of subjectivities, norms, and desires, also reminds us that democracy is not protected by institutions alone but by the moral and ethical frameworks that constitute the way citizens think about freedom, responsibility, and truth. Populist movements that promise to ‘give power back to the people’ tend to simplify complex problems, demonize pluralism, and replace moral reflection with emotional identification. The upshot is a democracy that has lost its normative aspiration and become a hollow procedural shell that can be manipulated.

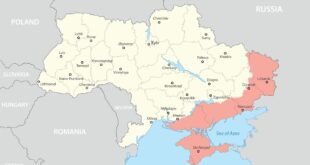

Take Hungary, Brazil, India, and the United States, where populist leaders have prevailed not just because of economic grievances or political alienation, but because they have rewritten the script of democracy. Elites are framed as corrupt, minorities as threatening, and themselves as the true voice of the ‘real’ people, reducing democratic legitimacy to a moral war where truth is secondary to loyalty and dissent is treason. In a digital age, social media amplifies echo chambers and speeds up the fragmentation of the public sphere, and the erosion of shared ethical ground is particularly dangerous. If every claim to truth is a partisan allegiance, democratic deliberation becomes impossible.

It would be a mistake to reduce this crisis to a mere failure of political leadership or media regulation. A deeper question is, what kind of moral community does democracy need in order to survive? Plato suspected democracy because he thought the masses, ruled by appetite and passion, were incapable of the rational deliberation that just rule required. His elitism is rightly rejected today, but his insistence that democracy needs ethical formation, that citizens need to be educated not only in rights but in virtues, is still profoundly relevant. Without civic education, without the common ground of truth, responsibility, and justice, democratic institutions become hollowed, and their formal procedures are easy prey for those who play on the public’s emotions.

The normative challenge, therefore, is to imagine democracy not only as a set of institutional safeguards but as an ongoing moral project that requires the active cultivation of civic virtues and ethical reflexivity. What does it mean to rebuild democratic cultures that resist the seductions of populism without lapsing into elitism? How do we generate spaces for pluralism, disagreement, and collective self-critique without falling into relativism or cynicism? These are not questions that can be solved by policy reforms or constitutional amendments; they require deep cultural work, educational investment, and a renewal of the public sphere as a space for moral and political contestation.

It is not merely a crisis of democracy but also of what kind of people we have become under democracy. It asks not just what institutions we need, but what sort of moral selves we must become to preserve democracy in the face of its most seductive enemies.

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense