Since the bloody partition of 1947, which birthed two nations with antagonistic identities, India and Pakistan have been locked in an existential rivalry where history, religion, and geopolitics intertwine. In this volatile equation, Kashmir, the epicenter of this perennial discord, remains an unresolved trauma, reignited by every skirmish and terrorist attack. By 2025, this centuries-old hostility has crossed a critical threshold. In South Asia’s fraught security landscape, nuclear doctrines are dangerously loosening, confidence-building mechanisms are eroding, and strategic alliances are deepening regional polarization. It has thus become imperative to rethink South Asian security paradigms. This analysis offers a deep dive into current dynamics and proposes pathways to avert a regional conflagration with incalculable consequences. However one frames it, the situation remains precarious and risks spiraling—a globalized world is not immune to such a clash.

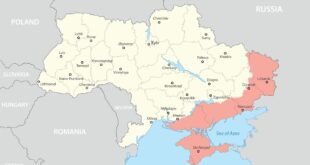

Rooted in decades of unresolved rivalry, the conflict has crystallized around Kashmir. A disputed territory, identity symbol, military flashpoint, and diplomatic lever. Thus, the recent developments, however, reveal a qualitative shift in this fault line. The April Pahalgam attack, which killed 26 civilians, dramatically reignited tensions. India accused Pakistan of backing the perpetrators, linked to the Resistance Front and Lashkar-e-Taiba. In response, New Delhi suspended the Indus Waters Treaty, closed the Attari-Wagah border crossing, and launched targeted strikes into Pakistan’s Punjab, shattering the implicit restraint that had prevailed since the 1999 Kargil War.

This near-catastrophic confrontation epitomizes the India-Pakistan strategic standoff. Triggered by Pakistani troops infiltrating Kargil’s high-altitude terrain, the conflict escalated into a war of attrition marked by positional battles and heavy casualties. This first war between declared nuclear powers exposed the fragility of ceasefire line control and the doctrinal instability on both sides. At the request of the Pakistani president, U.S. President Bill Clinton intervened directly. His involvement proved decisive, as the National Command Authority held substantial influence over political decisions. Under this pressure, Islamabad was ultimately forced to proceed with a unilateral withdrawal. Yet Kargil remains a case study in how localized crises can escalate into strategic shocks with real nuclear risks. In 2025, that threshold has been crossed, combining limited conventional warfare, asymmetric operations, information warfare, and identity-driven mobilization.

If Kargil exemplified high-attrition warfare, exposing porous borders and strike doctrine instability, today’s conflict cycle is far more diffuse. Following the Pahalgam attack, India launched Operation Sindoor, targeting alleged terrorist infrastructure. Pakistan retaliated with cross-border shelling, drone shoot-down claims, and cognitive warfare targeting India’s Muslim minorities. This is no longer frontal war but a fragmented, hybrid confrontation spanning cyber, media, and psychological domains—a destabilizing evolution that complicates crisis management exponentially.

Amid opaque doctrines, hybrid escalation, and absent credible mediation, the subcontinent drifts toward major strategic instability.

Beyond military posturing, this fault line has fueled decades of intellectual confrontation between Indian and Pakistani strategists, each crafting narratives on legitimacy, deterrence, and national security. On India’s side, former National Security Advisor Shivshankar Menon advocates «credible minimum deterrence» while questioning no-first-use nuclear orthodoxy. Conversely, General Khalid Kidwai, architect of Pakistan’s nuclear doctrine, frames atomic weapons as tools of preemptive stabilization. This doctrinal face-off sustains structural distrust, with each side interpreting the other’s signals as aggression preludes. The lack of a shared strategic lexicon or codified thresholds amplifies cognitive asymmetry. Thus, the India-Pakistan crisis becomes a war of ideas as much as a military standoff, where doctrinal concepts like «preemptive strike,» «massive retaliation,» and «undeclared thresholds» act as potential crisis accelerants.

This doctrinal gap—pitting India’s hierarchical deterrence against Pakistan’s tactical flexibility—fuels an environment clouded by what Clausewitz termed the «fog of war,» where perception often overrides reality. Compounding this opacity is Thomas Schelling’s theorized dynamic: escalation risks arise not from intent to harm but from misread deterrence signals. In such a climate, doctrinal ambiguity becomes an instability vector, erasing red lines, distorting adversarial assessments, and exposing every move to potential runaway escalation. Without reliable clarification channels, each show of resolve risks being perceived as aggression. In this hostile milieu, perception eclipses intent, driving tensions no party truly wishes to escalate.

The absence of convergence on nuclear thresholds, combined with asymmetric postures, renders military signal interpretation highly volatile. Routine exercises or deployments risk being misread as offensive preparation. Without agreements on alert postures or direct communication, signal decoding itself becomes a tension multiplier. Military history teaches that perceived vulnerability or advantage can trigger uncontrollable spirals. In South Asia, this dynamic is magnified by structural asymmetries in strategic decision-making. Pakistan’s power architecture—centralized under the military-dominated National Command Authority (NCA)—grants the army autonomous strategic latitude, as illustrated by the 1999 Kargil operation launched without Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s full coordination. India, conversely, relies on a civilian-military hierarchy where the National Security Council and political executive retain final authority, as seen in the tightly controlled 2019 Balakot surgical strikes. This command contrast sustains a thick strategic fog: India calibrates signals under political oversight, while Pakistan’s unpredictability heightens misinterpretation risks.

This divergence stems from power imbalances. Doctrines reflect real and perceived capabilities. The imbalance between India’s conventional superiority and Pakistan’s asymmetric logic shapes their strategic choices.

Militarily, India holds clear dominance. With 1.4 million troops, 4,200+ tanks (T-90, Arjun Mk1), 680+ combat aircraft (Su-30MKI, Rafale), and a carrier- and nuclear-submarine-equipped navy, its operational nuclear triad underscores conventional-nuclear synergy.

Pakistan, with 650,000 personnel, leans on preemptive deterrence. Its 160-warhead arsenal, Nasr/Shaheen-II/Ghauri missiles, and deliberately ambiguous «first-use» doctrine aim to offset conventional inferiority. However, this opacity, intended as a form of deterrence, increases the risk of misinterpretation. Islamabad’s hybrid reliance on non-state actors further destabilizes. Threshold breaches thus hinge not just on political intent but on how asymmetrically each side reads adversarial capabilities.

This doctrinal rift, rooted in asymmetric power and threat perceptions, reflects not just divergent deterrence philosophies but clashing cognitive frameworks. As doctrines grow flexible and less verifiable, strategic signal management frays, heightening misread risks. It is within this gray zone, both doctrinal and psychological, that South Asia’s deterrence architecture now encounters its most critical vulnerabilities. Amid strategic uncertainty, alliances gain critical importance. Beyond mere military pacts, they reshape power balances through regional influence, tech transfers, and containment strategies. India has built a strategic network transcending traditional partnerships to counterbalance China. As a Quad member (with the U.S., Japan, and Australia), it bolsters Indo-Pacific posture, complemented by defense ties with France (Scorpène submarines, Rafales) and Israel (drones, cyber, and missile defense). This tech-sharing, strategy-aligned architecture enhances India’s geopolitical depth and conventional deterrence against hybrid threats.

Pakistan remains anchored to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the Belt and Road Initiative’s crown jewel. Beyond granting China Indian Ocean access via Gwadar, CPEC traverses Gilgit-Baltistan—a region India claims as part of Jammu and Kashmir. New Delhi views CPEC as territorial provocation and Sino-Pakistani entrenchment. Islamabad also nurtures ties with Turkey, Iran, and Gulf states, blending security, ideology, and regionalism.

Moreover, Pakistan’s security posture no longer confines itself to defensive deterrence or operations within its own borders. In 2024, Pakistani airstrikes conducted in the Afghan provinces of Kunar and Khost, reportedly in response to alleged jihadist incursions, marked a doctrinal shift toward asserting extraterritorial strike capabilities. These operations, justified by a perceived threat and executed without prior regional coordination, set a troubling precedent. They underscore how Pakistan’s doctrine is increasingly moving toward a unilateral and preemptive interpretation of self-defense, further blurring red lines in a strategic environment already saturated with ambiguity.

However, the Bajwa Doctrine, led by former Army Chief Qamar Javed Bajwa, aimed to prioritize economic stabilization and regional integration, all while maintaining the military’s dominant influence over national policy. Despite framing economic partnerships (e.g., China, Gulf states) as tools to reduce India-centric rivalry, it failed to transform core conflict dynamics. Pakistan’s military retains control over Kashmir and nuclear policy, perpetuating distrust. While conciliatory rhetoric emerged, armed tensions persist, exposing economic initiatives’ inability to override territorial, identity, and security drivers. This modernization-security rigidity underscores hybrid strategy limits, where historical fractures and strategic calculus still trump de-escalation.

In short, Indian and Pakistani military doctrines embody antithetical deterrence visions. India’s «massive retaliation» doctrine clings (officially) to no-first-use; Pakistan’s «first-use» posture banks on ambiguity as a stabilizer. This gap raises persistent questions: How far will India stretch deterrence? How does Pakistan interpret limited incursions?

In this unstable deterrence architecture, nuclear weapons act as uncertainty multipliers, exacerbated by decision-making dynamics. Pakistan’s current Army Chief, General Asim Munir, embodies a more offensive line, contrasting with past military caution. Even limited Indian incursions could be seen as justifying tactical nuclear use. Absent bilateral de-escalation channels or strategic off-ramps, unpredictability grows. Meanwhile, external powers (U.S., China, UN) remain passive, urging restraint without crisis mediation.

Doctrinal Risks and Strategic Asymmetry

In the Indo-Pakistani strategic landscape, nuclear doctrines are neither static nor symmetrical. They are shaped by a structural imbalance that drives each actor to offset its vulnerabilities through flexible and, at times, ambiguous postures. India, bolstered by its conventional military superiority, upholds a doctrine of massive retaliation paired with an official no-first-use policy. Pakistan, by contrast, has developed a doctrine in response to India’s military advantage, designed to neutralize any conventional incursion at its earliest stage. This asymmetry creates an unstable doctrinal space in which the nuclear threshold is neither shared nor stabilized nor even mutually understood. This dynamic is precisely what Vipin Narang describes when analyzing asymmetric nuclear deterrence strategies. According to him, the militarily weaker actor tends to adopt a more aggressive doctrinal posture, deliberately lowering its nuclear threshold to bolster the credibility of its deterrence. However, such asymmetry undermines crisis management, as the more ambiguous and preemptive a doctrine becomes, the higher the risk of provoking an overreaction from the adversary.

Zachary Keck and Toby Dalton highlight risks from threshold ambiguity. In communication-starved conflict zones, non-codified doctrines fuel perpetual psychological warfare, where adversarial postures’ perception outweighs reality. Defensive exercises become aggression signals; shows of force read as imminent provocation.

Thus, several strategic trajectories could emerge from the current climate of tension, each carrying distinct implications for regional and global stability. One potential outcome involves a phase of managed escalation that, through restrained confrontation and backchannel diplomacy, ultimately reverts to a fragile but familiar status quo. Another possibility is the evolution of a prolonged hybrid crisis, marked by intermittent skirmishes, disinformation campaigns, and cyber operations that keep both sides in a state of persistent confrontation without crossing into full-scale war. The most alarming scenario, though less likely in the short term, remains the outbreak of a limited nuclear conflict, not necessarily by deliberate intent but as a result of misperceived signals, miscalculated risk-taking, or unanticipated escalation. In a region where strategic doctrines are opaque and thresholds remain ill-defined, even a minor misstep could unravel existing deterrence frameworks and propel South Asia, and potentially the wider international community, into a crisis of unprecedented scale and uncertainty.

Therefore, in light of these destabilizing trajectories, the need for robust de-escalation mechanisms becomes more urgent than ever. Establishing reliable communication channels, enhancing transparency in doctrinal intentions, and promoting confidence-building measures are not merely diplomatic niceties but essential tools to prevent inadvertent catastrophe. Without such safeguards, the Indo-Pakistani rivalry risks becoming a perpetual crisis engine, where ambiguity fuels brinkmanship and restraint becomes the exception rather than the norm.

It is time to transcend classical frameworks and propose a South Asian stability architecture. This should include de-escalation mechanisms, reinforced hotlines, credible neutral mediation, and a «Regional Nuclear Code of Conduct» clarifying doctrines. The code would not disarm but rationalize deterrence, preventing misinterpretation or uncontrolled brinkmanship.

Long-term stability hinges on gradual economic integration via trade corridors, energy cooperation, and climate initiatives to foster stabilizing interdependence. In a subcontinent marked by unregulated nuclear rivalry, stability can no longer rely on mutual deterrence or improvised restraint. Doctrinal opacity and perceptual volatility make each crisis riskier than the last. Breaking this cycle demands moving beyond crisis management orthodoxy.

For these reasons, a «South Asian Helsinki,» modeled on Europe’s CSCE, could offer a structured, apolitical regional dialogue forum. It would build minimal doctrinal transparency, incident notification systems, and coordinated border management. Over time, such a platform could revive strategic diplomacy in a theater dominated by force demonstrations. South Asia’s stability now hinges on nuclear rivals’ ability to frame their rivalry within an interpretable, communicable, verifiable framework. The era of mere deterrence is over; the age of managed strategic innovation has begun.

In deterrence’s gray zones, lawlessness multiplies irreversibility risks. Without structured dialogue on thresholds, doctrines, and controls, Indo-Pak crisis management remains improvised. Unlike Cold War Europe, South Asia lacks credible multilateral nuclear regulation. Deterrence alone is obsolete; strategic boldness is essential. As Henry Kissinger noted, “Nuclear weapons may not be usable, but they shape every calculation short of war.” In South Asia, nukes shape all interactions, from military drills to diplomatic postures. They turn local crises into irreversible threshold tests. Until institutional mechanisms tame this prism, every incident risks catastrophe. In this gray zone, anarchy doesn’t expand freedom; it heightens disaster risks. Against a rivalry where intensity eclipses clarity, only managed strategic innovation can avert worst-case logic.

Ultimately, the region serves as a stark reminder that in the nuclear age, even so-called «frozen» conflicts can ignite with devastating consequences, and history repeats itself only until it spirals out of control. Preventing catastrophe now requires a bold overhaul of trust-building mechanisms, ideally through multilateral mediation involving actors such as the United Nations, Nordic countries, or ASEAN. In parallel, advancing economic interdependence through initiatives like cross-border solar grids and cooperative water management could help generate shared interests and raise the cost of conflict to prohibitive levels. While these measures may seem ambitious, they are far less utopian than the alternative—a scenario of uncontrolled escalation in which opaque doctrines and entrenched hostilities erode the very foundations of deterrence. In the India-Pakistan equation, the current equilibrium is little more than a fragile illusion, and strategic improvisation risks becoming a path to mutual destruction.

Given these realities, it is imperative to stress: absent shared doctrinal frameworks, Indo-Pak deterrence ceases to be a safeguard. It becomes a trap. For in asymmetric rivalries, it is not the weapon that triggers war but the illusion of controlling it.

In South Asia’s nuclear geometry, deterrence is no longer a stabilizer; it is a shifting mirage. And in a world where perception moves faster than diplomacy, miscalculation is not a possibility; it is a countdown.

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense