Nabih Bulos , W.J. Hennigan and Brian Bennett

Syrian militias armed by different parts of the U.S. war machine have begun to fight each other on the plains between the besieged city of Aleppo and the Turkish border, highlighting how little control U.S. intelligence officers and military planners have over the groups they have financed and trained in the bitter five-year-old civil war.

The fighting has intensified over the last two months, as CIA-armed units and Pentagon-armed ones have repeatedly shot at each other while maneuvering through contested territory on the northern outskirts of Aleppo, U.S. officials and rebel leaders have confirmed.

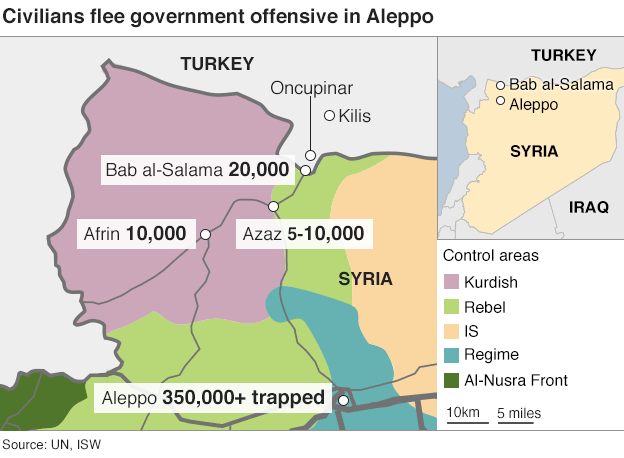

In mid-February, a CIA-armed militia called Fursan al Haq, or Knights of Righteousness, was run out of the town of Marea, about 20 miles north of Aleppo, by Pentagon-backed Syrian Democratic Forces moving in from Kurdish-controlled areas to the east.

“Any faction that attacks us, regardless from where it gets its support, we will fight it,” Maj. Fares Bayoush, a leader of Fursan al Haq, said in an interview.

Rebel fighters described similar clashes in the town of Azaz, a key transit point for fighters and supplies between Aleppo and the Turkish border, and on March 3 in the Aleppo neighborhood of Sheikh Maqsud.

The attacks by one U.S.-backed group against another come amid continued heavy fighting in Syria and illustrate the difficulty facing U.S. efforts to coordinate among dozens of armed groups that are trying to overthrow the government of President Bashar Assad, fight the Islamic State militant group and battle one another all at the same time.

“It is an enormous challenge,” said Rep.Adam Schiff (D-Burbank), the top Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee, who described the clashes between U.S.-supported groups as “a fairly new phenomenon.”

“It is part of the three-dimensional chess that is the Syrian battlefield,” he said.

The area in northern Syria around Aleppo, the country’s second-largest city, features not only a war between the Assad government and its opponents, but also periodic battles against Islamic State militants, who control much of eastern Syria and also some territory to the northwest of the city, and long-standing tensions among the ethnic groups that inhabit the area, Arabs, Kurds and Turkmen.

“This is a complicated, multi-sided war where our options are severely limited,” said a U.S. official, who wasn’t authorized to speak publicly on the matter. “We know we need a partner on the ground. We can’t defeat ISIL without that part of the equation, so we keep trying to forge those relationships.” ISIL is an acronym for Islamic State.

President Obama this month authorized a new Pentagon plan to train and arm Syrian rebel fighters, relaunching a program that was suspended in the fall after a string of embarrassing setbacks which included recruits being ambushed and handing over much of their U.S.-issued ammunition and trucks to an Al Qaeda affiliate.

Amid the setbacks, the Pentagon late last year deployed about 50 special operations forces to Kurdish-held areas in northeastern Syria to better coordinate with local militias and help ensure U.S.-backed rebel groups aren’t fighting one another. But such skirmishes have become routine.

Last year, the Pentagon helped create a new military coalition, the Syrian Democratic Forces. The goal was to arm the group and prepare it to take territory away from the Islamic State in eastern Syria and to provide information for U.S. airstrikes.

The group is dominated by Kurdish outfits known as People’s Protection Units or YPG. A few Arab units have joined the force in order to prevent it from looking like an invading Kurdish army, and it has received air-drops of weapons and supplies and assistance from U.S. Special Forces.

Gen. Joseph Votel, now commander of U.S. Special Operations Command and the incoming head of Central Command, said this month that about 80% of the fighters in the Syrian Democratic Forces were Kurdish. The U.S. backing for a heavily Kurdish armed force has been a point of tension with the Turkish government, which has a long history of crushing Kurdish rebellions and doesn’t want to see Kurdish units control more of its southern border.

The CIA, meanwhile, has its own operations center inside Turkey from which it has been directing aid to rebel groups in Syria, providing them with TOW antitank missiles from Saudi Arabian weapons stockpiles.

While the Pentagon’s actions are part of an overt effort by the U.S. and its allies against Islamic State, the CIA’s backing of militias is part of a separate covert U.S. effort aimed at keeping pressure on the Assad government in hopes of prodding the Syrian leader to the negotiating table.

At first, the two different sets of fighters were primarily operating in widely separated areas of Syria — the Pentagon-backed Syrian Democratic Forces in the northeastern part of the country and the CIA-backed groups farther west. But over the last several months, Russian airstrikes against anti-Assad fighters in northwestern Syria have weakened them. That created an opening which allowed the Kurdish-led groups to expand their zone of control to the outskirts of Aleppo, bringing them into more frequent conflict with the CIA-backed outfits.

“Fighting over territory in Aleppo demonstrates how difficult it is for the U.S. to manage these really localized and in some cases entrenched conflicts,” said Nicholas A. Heras, an expert on the Syrian civil war at the Center for a New American Security, a think tank in Washington. “Preventing clashes is one of the constant topics in the joint operations room with Turkey.”

Over the course of the Syrian civil war, the town of Marea has been on the front line of Islamic State’s attempts to advance across Aleppo province toward the rest of northern Syria.

On Feb. 18, the Syrian Democratic Forces attacked the town. A fighter with the Suqour Al-Jabal brigade, a group with links to the CIA, said intelligence officers of the U.S.-led coalition fighting Islamic State know their group has clashed with the Pentagon-trained militias.

“The MOM knows we fight them,” he said, referring to the joint operations center in southern Turkey, using an abbreviation for its name in Turkish, Musterek Operasyon Merkezi. “We’ll fight all who aim to divide Syria or harm its people.” The fighter spoke on condition of anonymity.

Marea is home to many of the original Islamist fighters who took up arms against Assad during the Arab Spring in 2011. It has long been a crucial way station for supplies and fighters coming from Turkey into Aleppo.

“Attempts by Syrian Democratic Forces to take Marea was a great betrayal and was viewed as a further example of a Kurdish conspiracy to force them from Arab and Turkmen lands,” Heras said.

The clashes brought the U.S. and Turkish officials to “loggerheads,” he added. After diplomatic pressure from the U.S., the militia withdrew to the outskirts of the town as a sign of good faith, he said.

But continued fighting among different U.S.-backed groups may be inevitable, experts on the region said.

“Once they cross the border into Syria, you lose a substantial amount of control or ability to control their actions,” Jeffrey White, a former Defense Intelligence Agency official, said in a telephone interview. “You certainly have the potential for it becoming a larger problem as people fight for territory and control of the northern border area in Aleppo.”

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense