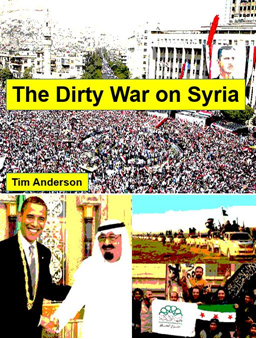

The following text is the introductory chapter of Professor Tim Anderson’s forthcoming book entitled The Dirty War on Syria

Although every war makes ample use of lies and deception, the dirty war on Syria has relied on a level of mass disinformation not seen in living memory. The British-Australian journalist Philip Knightley pointed out that war propaganda typically involves ‘a depressingly predictable pattern’ of demonising the enemy leader, then demonising the enemy people through atrocity stories, real or imagined (Knightley 2001). Accordingly, a mild-mannered eye doctor called Bashar al Assad became the new evil in the world and, according to consistent western media reports, the Syrian Army did nothing but kill civilians for more than four years. To this day, many imagine the Syrian conflict is a ‘civil war’, a ‘popular revolt’ or some sort of internal sectarian conflict. These myths are, in many respects, a substantial achievement for the big powers which have driven a series of ‘regime change’ operations in the Middle East region, all on false pretexts, over the past 15 years.

In 2011 I had only a basic understanding of Syria and its history. However I was deeply suspicious when reading of the violence that erupted in the southern border town of Daraa. I knew that such violence (sniping at police and civilians, the use of semi-automatic weapons) does not spring spontaneously from street demonstrations. And I was deeply suspicious of the big powers. All my life I had been told lies about the pretexts for war. I decided to research the Syrian conflict, reading hundreds of books and articles, watching many videos and speaking to as many Syrians as I could. I wrote dozens of articles and visited Syria twice, during the conflict. This book is a result of that research.This book is a careful academic work, but also a strong defence of the right of the Syrian people to determine their own society and political system. That position is consistent with international law and human rights principles, but may irritate western sensibilities, accustomed as we are to an assumed prerogative to intervene. At times I have to be blunt, to cut through the double-speak. In Syria the big powers have sought to hide their hand, using proxy armies while demonising the Syrian Government and Army, accusing them of constant atrocities; then pretending to rescue the Syrian people from their own government. Far fewer western people opposed the war on Syria than opposed the invasion of Iraq, because they were deceived about its true nature.

Dirty wars are not new. Cuban national hero Jose Martí predicted to a friend that Washington would try to intervene in Cuba’s independence struggle against the Spanish. ‘They want to provoke a war’, he wrote in 1889 ‘to have a pretext to intervene and, with the authority of being mediator and guarantor, to seize the country … There is no more cowardly thing in the annals of free people; nor such cold blooded evil’ (Martí 1975: 53). Nine years later, during the third independence war, an explosion in Havana Harbour destroyed the USS Maine, killing 258 US sailors and serving as a pretext for a US invasion.

The subsequent ‘Spanish-American’ war snatched victory from the Cubans and allowed the US to take control of the remaining Spanish colonial territories. Cuba had territory annexed and a deeply compromised constitution was imposed. No evidence ever proved the Spanish were responsible for the bombing of the Maine and many Cubans believe the North Americans bombed their own ship. The monument in Havana, in memory of those sailors, still bears this inscription: ‘To the victims of the Maine who were sacrificed to imperialist voracity and the desire to gain control of the island of Cuba’ (Richter 1998).

The US launched dozens of interventions in Latin America over the subsequent century. A notable dirty war was led by CIA-backed, ‘freedom fighter’ mercenaries based in Honduras, who attacked the Sandinista Government and the people of Nicaragua in the 1980s. That conflict, in its modus operandi, was not so different to the war on Syria. In Nicaragua more than 30,000 people were killed. The International Court of Justice found the US guilty of a range of terrorist-style attacks on the little Central American country, and found that the US owed Nicaragua compensation (ICJ 1986). Washington ignored these rulings.

With the ‘Arab Spring’ of 2011 the big powers took advantage of a political foment by seizing the initiative to impose an ‘Islamist winter’, attacking the few remaining independent states of the region. Very quickly we saw the destruction of Libya, a small country with the highest standard of living in Africa. NATO bombing and a Special Forces campaign helped the al Qaeda groups on the ground. The basis for NATO’s intervention was lies told about actual and impending massacres, supposedly carried out or planned by the government of President Muammar Gaddafi. These claims led rapidly to a UN Security Council resolution said to protect civilians through a ‘no fly zone’. We know now that trust was betrayed, and that the NATO powers abused the limited UN authorisation to overthrow the Libyan Government (McKinney 2012).

Subsequently, no evidence emerged to prove that Gaddafi intended, carried out or threatened wholesale massacres, as was widely suggested (Forte 2012). Genevieve Garrigos of Amnesty International (France) admitted there was ‘no evidence’ to back her group’s earlier claims that Gaddafi had used ‘black mercenaries’ to commit massacres (Forte 2012; Edwards 2013).

Alan Kuperman, drawing mainly on North American sources, demonstrates the following points. First, Gaddafi’s crackdown on the mostly Islamist insurrection in eastern Libya was ‘much less lethal’ than had been suggested. Indeed there was evidence that he had had ‘refrained from indiscriminate violence’. The Islamists were themselves armed from the beginning. From later US estimates, of the almost one thousand casualties in the first seven weeks, about three percent were women and children (Kuperman 2015). Second, when government forces were about to regain the east of the country, NATO intervened, claiming this was to avert an impending massacre. Ten thousand people died after the NATO intervention, compared to one thousand before. Gaddafi had pledged no reprisals in Benghazi and ‘no evidence or reason’ came out to support the claim that he planned mass killings (Kuperman 2015). The damage was done. NATO handed over the country to squabbling groups of Islamists and western aligned ‘liberals’. A relatively independent state was overthrown, but Libya was destroyed. Four years on there is no functioning government and violence persists; and that war of aggression against Libya went unpunished.

Two days before NATO bombed Libya another armed Islamist insurrection broke out in Daraa, Syria’s southernmost city. Yet because this insurrection was linked to the demonstrations of a political reform movement, its nature was disguised. Many did not see that those who were providing the guns – Qatar and Saudi Arabia – were also running fake news stories in their respective media channels, Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya. There were other reasons for the durable myths of this war. Many western audiences, liberals and leftists as well as the more conservative, seemed to like the idea of their own role as the saviours of a foreign people, speaking out strongly about a country of which they knew little, but joining what seemed to be a ‘good fight’ against this new ‘dictator’. With a mission and their proud self-image western audiences apparently forgot the lies of previous wars, and of their own colonial legacies.

I would go so far as to say that, in the Dirty War on Syria, western culture in general abandoned its better traditions: of reason, the maintenance of ethical principle and the search for independent evidence at times of conflict; in favour of its worst traditions: the ‘imperial prerogative’ for intervention, backed by deep racial prejudice and poor reflection on the histories of their own cultures. That weakness was reinforced by a ferocious campaign of war propaganda. After the demonisation of Syrian leader Bashar al Assad began, a virtual information blockade was constructed against anything which might undermine the wartime storyline. Very few sensible western perspectives on Syria emerged after 2011, as critical voices were effectively blacklisted.

In that context I came to write this book. It is a defence of Syria, not primarily addressed to those who are immersed the western myths but to others who engage with them. This is therefore a resource book and a contribution to the history of the Syrian conflict. The western stories have become self-indulgent and I believe it is wasteful to indulge them too much. Best, I think, to speak of current events as they are, then address the smokescreens later. I do not ignore the western myths, in fact this book documents many of them. But I lead with the reality of the war.

Western mythology relies on the idea of imperial prerogatives, asking what must ‘we’ do about the problems of another people; an approach which has no basis in international law or human rights. The next steps involve a series of fabrications about the pretexts, character and events of the war. The first pretext over Syria was that the NATO states and the Gulf monarchies were supporting a secular and democratic revolution. When that seemed implausible the second story was that they were saving the oppressed majority ‘Sunni Muslim’ population from a sectarian ‘Alawite regime’. Then, when sectarian atrocities by anti-government forces attracted greater public attention, the pretext became a claim that there was a shadow war: ‘moderate rebels’ were said to be actually fighting the extremist groups. Western intervention was therefore needed to bolster these ‘moderate rebels’ against the ‘new’ extremist group that had mysteriously arisen and posed a threat to the world.

That was the ‘B’ story. No doubt Hollywood will make movies based on this meta-script, for years to come. However this book leads with the ‘A’ story. Proxy armies of Islamists, armed by US regional allies (mainly Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey), infiltrate a political reform movement and snipe at police and civilians. They blame this on the government and spark an insurrection, seeking the overthrow of the Syrian government and its secular-pluralist state. This follows the openly declared ambition of the US to create a ‘New Middle East’, subordinating every country of the region, by reform, unilateral disarmament or direct overthrow. Syria was next in line, after Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya. In Syria, the proxy armies would come from the combined forces of the Muslim Brotherhood and Saudi Arabia’s Wahhabi fanatics. Despite occasional power struggles between these groups and their sponsors, they share much the same Salafist ideology, opposing secular or nationalist regimes and seeking the establishment of a religious state.

However in Syria Washington’s Islamists confronted a disciplined national army which did not disintegrate along religious lines, despite many provocations. The Syrian state also had strong allies in Russia and Iran. Syria was not to be Libya Take Two. In this prolonged war the violence, from the western side, was said to consist of the Syrian Army targeting and killing civilians. From the Syrian side people saw daily terrorist attacks on towns and cities, schools and hospitals and massacres of ordinary people by NATO’s ‘freedom fighters’, then the counter attacks by the Army. Foreign terrorists were recruited in dozens of countries by the Saudis and Qatar, bolstering the local mercenaries.

Though the terrorist groups were often called ‘opposition, ‘militants’ and ‘Sunni groups’ outside Syria, inside the country the actual political opposition abandoned the Islamists back in early 2011. Protest was driven off the streets by the violence, and most of the opposition (minus the Muslim Brotherhood and some exiles) sided with the state and the Army, if not with the ruling Ba’ath Party. The Syrian Army has been brutal with terrorists but, contrary to western propaganda, protective of civilians. The Islamists have been brutal with all, and openly so. Millions of internally displaced people have sought refuge with the Government and Army, while others fled the country.

In a hoped-for ‘end game’ the big powers sought overthrow of the Syrian state or, failing that, the creation of a dysfunctional state or dismembering into sectarian statelets, thus breaking the axis of independent regional states. That axis comprises Hezbollah in south Lebanon and the Palestinian resistance, alongside Syria and Iran, the only states in the region without US military bases. More recently Iraq – still traumatised from western invasion, massacres and occupation – has begun to align itself with this axis. Russia too has begun to play an important counter-weight role. Recent history and conduct demonstrate that neither Russia nor Iran harbour any imperial ambitions remotely approaching those of Washington and its allies, several of which (Britain, France and Turkey) were former colonial warlords in the region. From the point of view of the ‘Axis of Resistance’, defeat of the dirty war on Syria means that the region can begin closing ranks against the big powers. Syria’s successful resistance would mean the beginning of the end for Washington’s ‘New Middle East’.

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense