Beijing is preparing its people for hardship and explaining the necessity of a protracted national struggle against Washington.

There is little dispute that China engages in unfair and often predatory practices to protect and promote its domestic industries. Yet if the Trump administration’s diagnosis of U.S.-China economic relations is correct, its remedy has been roundly rejected. Most observers believe the U.S. resort to unilateral tariffs will fail to achieve its intended objectives and will harm the U.S. economy as much as China’s. Furthermore, this episode may have the negative long-term effect of strengthening China’s confidence that it will prevail in future bilateral tests of will.

In public discussion of the U.S.-China trade relationship, President Donald Trump has focused on China’s huge surplus in bilateral trade—$419 billion in 2018—as proof the Chinese are “cheating” and “raping” the U.S. economy. Many economists have criticized Trump for an overly simplistic if not erroneous fixation on the trade balance as the key issue in bilateral economic relations. Senior Trump advisors, such as U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, have instead emphasized a broader goal of getting China to address structural problems such as protectionism against foreign-service industries, state subsidization of much of the Chinese economy, state-sponsored industrial espionage and acquiescence to intellectual property theft, and forced technology transfer as the price foreigners must pay to do business in China. This approach enjoys support from businesses in the United States and elsewhere that want to break into the Chinese market.

To address the trade imbalance, the United States in 2018 imposed tariffs sequentially on three “lists” of goods from China, first targeting $34 billion in annual imports, then another $16 billion, and finally an additional $200 billion. As the dispute has dragged on, U.S. tariff rates have increased, and Trump now threatens to sanction virtually all imports from China. Beijing has retaliated with sanctions of its own, and said it would raise tariffs from 10 percent to 20–25 percent on the roughly $60 billion in U.S. exports to China already being taxed.

President Trump said he believes a trade war is “good and easy to win.” Virtually all experts disagree. The International Monetary Fund has concluded that U.S. and Chinese consumers are “unequivocally the losers” in a trade war. The Peterson Institute for International Economics estimates that existing tariffs on Chinese imports cost U.S. families about $550, a sum that will rise to $2,200 if the administration raises tariffs to 25 percent on $500 billion of Chinese imports as threatened. Another study reckons the net loss would exceed 2.2 million jobs if all tariffs continue and cause a sales decline. One indication of the impact in the United States is the Trump administration’s payment of over $8.5 billion to farmers to offset losses resulting from the trade war and the promise of another multibillion tranche of aid. Goldman Sachs anticipates an escalating trade war will trim U.S. economic growth by 0.4 percent, and perhaps more if it impacts the stock market. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has forecast a $1 trillion loss if the trade war continues for a decade.

China is being hurt, too. Food price inflation has jumped substantially since the trade war began. There is anecdotal evidence of workers being laid off and consumer spending declining. According to simulations by Japan’s Institute of Developing Economies, in a trade war that lasts for three years and includes 25 percent additional tariffs on all goods imported from each other, the U.S. economy will take a 0.4 percent hit; China’s is bigger at 0.6 percent.

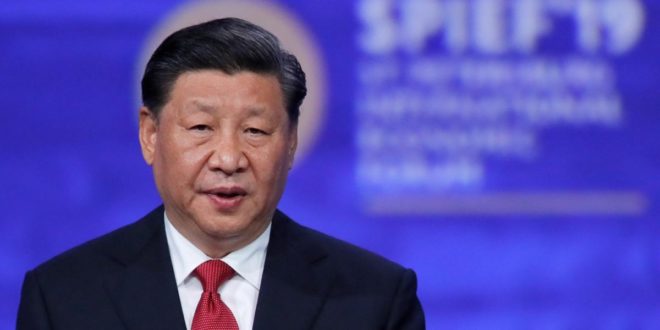

Contrary to President Trump’s claims, it will not be “easy” to get China to substantially dismantle its unfair trade and investment policies through the imposition of tariffs; in fact it will be extremely difficult. Meeting U.S. demands for structural change would compromise some of the principal levers by which the Chinese Communist Party manages its monopoly over political power in China. Maintaining party control over society is one area where Chinese leaders do not compromise, as the world saw all too clearly thirty years ago. Xi must worry about preserving his image at home as the protector of Chinese interests and honor in a dispute where most Chinese believe U.S. demands are unfair and simply reflect U.S. unwillingness to accept Chinese success. Xi likely has the burden of higher public expectations that he will win a dispute with the United States than his predecessors had. He presides over the era of a post-Deng “assertive” China that its citizens increasingly presume will prevail when challenged by foreigners. The personality cult that he has cultivated since taking power makes losses in foreign-policy battles even more glaring.

Accordingly, the Chinese government is mobilizing for tough resistance. While the official Chinese government reaction is to downplay the impact of the trade fight—typical is a comment by Wang Zhijun, vice minister of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, who insists that the impact of the U.S. tariffs will be “manageable”—other government actions suggest otherwise. The Central Bank continues to cut bank reserve requirements to ensure that lenders have money to lend if the economy turns downward. Beijing has established a special task force, the State Council Employment Work Leading Group, to monitor job losses resulting from the trade war. The Ministry of Commerce announced that it was developing an “unreliable entity list” of foreign entities and individuals that are deemed to have damaged Chinese firms or posed a threat to national security. The threat to cut off rare earths exports, so far only mooted in media such as the People’s Daily, is a clear signal of the seriousness of the situation. Many U.S. businesses in China report they are suffering from administrative harassment—a common tactic of Chinese officialdom—as a consequence of the tariff war.

In contrast to Trump’s false assurances to the U.S. public, the Chinese government is preparing its own people for hardship and explaining the necessity of a protracted national struggle against the United States. The rhetoric of Vice Foreign Minister Zhang Hanhui hits all the right buttons when he calls the U.S. actions “naked economic terrorism, economic chauvinism, and economic bullying.” That echoes President Xi Jinping’s call for a new “Long March” in a recent appearance—at a rare earths processing facility, no less—to rally the nation against a foreign bully. And if that was too subtle, state television has been showing patriotic movies about the Korean War, when China last “defeated” U.S. aggressors. A Xinhua editorial reminded readers that “The Chinese are people who have a great spirit of struggle. History has shown that hardships only strengthen the Chinese people’s determination to fight and hone their ability to win. . . . let it be clear that no outside forces can stop China from reaching the Chinese Dream of national rejuvenation.”

The patriotic bloviations of the Chinese media highlight the psychological warfare advantage that Beijing enjoys as an authoritarian state with a controlled press that serves the government’s agenda. The U.S. media freely reports on how tariffs are hurting Americans, while there is nothing comparable from the Chinese side. A People’s Daily editorial notes that “Washington’s reckless leap in the dark has been poured with strong opposition and condemnation from domestic society. The American Soybean Association, American Apparel & Footwear Association, the U.S. Consumer Technology Association, the National Retail Federation and other walks of life warned that it would roil the markets, hurt the interests of consumers, workers, farmers and companies, and severely jeopardize US economy.” Ultimately, the tariff war is largely about which of the two sides can best endure the pain both are suffering. China’s is largely hidden, while America’s is so openly and abundantly discussed as to feed national demoralization.

China can be expected to use Trump’s goal of re-election in 2020 to lure him into a settlement that is comparatively painless for Beijing. Look for the crisis to end with China meeting the minimal U.S. demand—addressing Trump’s main concern—by promising to buy a couple hundred billion dollars of additional U.S. exports and (insincerely) promising to look into the structural issues. This would allow Trump to pocket a quick “victory” prior to the 2020 vote, call a truce in the trade war, and return to business as usual. That would allow Beijing to ignore demands that it privatize its economy, open decisively to foreign competition in now-protected sectors, and give up the practice of stealing or extorting advanced technology.

The Trump administration was right to confront China’s systematic economic predation, but its chosen approach has little chance of meaningful success. Worse, Beijing could well emerge from this experience convinced that the United States is unable to stand up for its own interests because of the irresistible appeal of the Chinese market and the inability of Americans to endure even short-term hardship. This outcome would likely reinforce the Chinese view of the United States as a weakening and dysfunctional country. Also, it would amplify Beijing’s boldness in challenging Washington across a range of issues.

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense