Nicholas Eberstadt

Like it or not, it was a triumph of statecraft.

he remarkable truth about the “North Korean nuclear crisis” is that the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea — a tiny, isolated, and impoverished state — has been almost completely in charge of it since the global drama erupted almost three decades ago. The DPRK has determined both the tempo of events and the details of international diplomacy, right down to the conference agendas: what parties would meet, when and where the meetings would take place, and even what would be discussed. This is a drama with a purpose, for the outcome of this ongoing “crisis” has been the steady march of a most unlikely candidate into the ranks of the nuclear-weapons states.

The Kim-family regime and its notorious peculiarities are endlessly mocked in the outside world. Be that as it may: A remote, closed-off, and seemingly buffoonish dictatorship has demonstrated time and again that it understands more about global power politics than do its powerful and purportedly sophisticated adversaries.

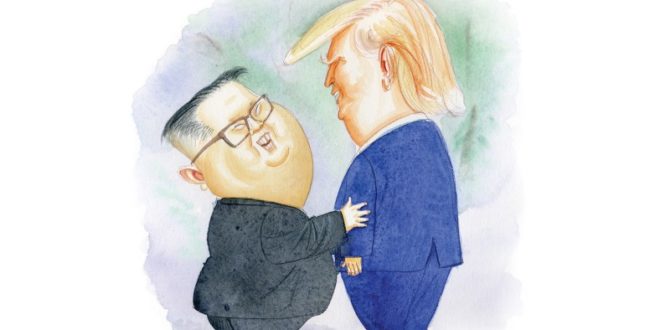

This month’s U.S.–North Korean summit in Singapore marks a truly historic milestone on the DPRK’s road to establishing itself as a permanent nuclear power. Whether Washington recognizes it yet or not, the encounter was a victory for Pyongyang — and a big one. Indeed, it is hard to think of any greater diplomatic coup for the North Korean regime since 1950, when missions to Moscow by “Great Leader” Kim Il-sung (grandfather to the current “Dear Respected Leader”) secured Stalin’s permission for a surprise attack on South Korea.

With a single stroke in Singapore, Kim Jong-un apparently defanged President Donald Trump, North Korea’s most formidable American opponent in the post–Cold War era; consolidated the recent advances in the DPRK’s nuke and missile programs; and positioned North Korea to reap even greater gains from its high-tension, long-term game plan in the months and years ahead. The Singapore summit, in other words, looks to have been a signal step toward making the world safe for Kim Jong-un and his regime.

The DPRK was born as a Stalinist satellite state in the aftermath of World War II, but unlike the captive nations on the Soviet Union’s western borders, it broke free of the Kremlin’s orbit early on and gradually implemented a dramatically different sort of totalitarian despotism. This metamorphosis helps explain why the North Korean regime survived when the USSR and all of the other Soviet satellites collapsed.

It is not just that the DPRK diligently and exquisitely improved upon — one is tempted to say perfected — the domestic mechanisms of police-state control and terror that were its Stalinist patrimony, or that it managed to effect a historically unprecedented long-term militarization, setting its society and economy on something approaching a full war footing these past 50 years and more. The state also mutated into that most un-Marxian of political arrangements, an Asiatic dynasty replete with hereditary rule.

Absolute and unconditional reunification of Korea under the authority of the Kim regime, then, is imperative — and nonnegotiable. This is not some bargaining chip to be horse-traded away for better terms on some other items of interest to North Korean leadership. The call for unconditional reunification stands as a central and sacred mission for the North Korean state. The inconvenient existence of the government of the Republic of Korea stands very much in the way of Pyongyang’s vision of a peninsula-wide racial utopia; thus the South Korean state must be erased from the face of the earth.

Why is it so crucial to North Korean leadership to “mass-produce nuclear warheads and missiles and speed up their deployment,” as Kim Jong-un announced his government was doing in his New Year’s Day Address earlier this year? Such a program would not be necessary for regime legitimation, or for international military extortion, or even to ensure the regime’s survival: All of those objectives could surely be satisfied with a limited nuclear force. Why then threaten the U.S. homeland?

Quite simply, because Uncle Sam is the longstanding guarantor of South Korean security — and if Uncle Sam can be forced to blink in a crisis of Pyongyang’s making, at a place and time of Pyongyang’s choosing, the U.S.–ROK alliance will collapse, America’s security presence in the Korean Peninsula will end, and North Korea will be closer to unconditional reunification than it has been at any point since the summer of 1950.

Just to be clear: North Korean absorption of the South would hardly be a foregone conclusion even in such a hypothetical scenario. The South is much more populous, vastly more productive, far more technologically advanced, and capable of becoming a nuclear power quickly. Yet North Korean leadership appears convinced that the South is hopelessly corrupt, pampered, and gutless, and that it would ultimately lack the will to resist a forced reunification.

Severing the U.S.–ROK security alliance is the sine qua non for the North’s grand vision of reunification — and amassing a powerful nuke and missile force is the sine qua non for severing the U.S.–ROK security alliance. In earlier times, when the South was weaker and the North was stronger, other paths might have appeared feasible, including another full-frontal conventional military assault. But today, nukes and missiles look to be the only option.

If we understand this, we also understand how unrealistic any expectation of a voluntary North Korean denuclearization must be.

America’s sorry record on North Korean nuclear proliferation stems in large part from its failure to see North Korea as it actually exists and its attempt to deal with an imaginary, much more tractable North Korea instead. From Bush 41 through Obama, an unbroken string of U.S. administrations focused on resolving the issue through international negotiations. They missed the fact that North Korea regards international negotiations as war by other means. To make a long, sad saga short, American negotiators were consistently wrong-footed, fooled, and flummoxed by their North Korean counterparts, not only because the DPRK negotiators were almost invariably better prepared (having “war-gamed” these meetings in advance), but also because the North had no compunction about negotiating in bad faith.

North Korean leaders perfected an extraordinarily effective routine for breaking through Western nonproliferation strictures: First, push nuclear and missile programs forward as fast as possible, either furtively or through brazen open testing. Second, make aggressive and ominous noises when confronted, giving hints that the Korean Peninsula is on the verge of war. Third, suddenly change from bellicose to conciliatory, graciously agree to international conferences, use said conferences to consolidate and secure official recognition of the newest North Korean gains, and agree to a few points of interest to the foreigners with no intention of honoring them. Fourth, repeat.

Americans, to be sure, were not the only ones suckered by the illusory prospect of “getting to yes” with Pyongyang: The South Koreans, Japanese, and others took the bait too, some repeatedly. But traducing the U.S. is always most important, considering Washington’s adversarial relationship with Pyongyang, its unrivaled international power, and its indispensable role in the security architecture of Northeast Asia and the world.

Donald Trump came to office intent on upending the perverse modus operandi under which his predecessors, Republicans and Democrats alike, had haplessly watched the North Korean threat grow bigger and more menacing. He replaced Obama’s passive-aggressive lassitude with an active and assertive policy, one that accorded the North Korean threat a top ranking among U.S. security concerns and attempted to reduce the threat systematically. Through defensive military measures, energized economic sanctions, alliance-strengthening and coalition-building, elevating the prominence of North Korean human-rights issues internationally, and more, Trump and his team fashioned an approach that promised to reduce the North Korean threat.

While international-trade figures are by no means perfect, they suggest that Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign has sharply constricted the flows of commercial merchandise into North Korea and North Korea’s revenues from commercial exports — and since the North Korean economy is exceptionally distorted and dependent upon outside resources, such sanctions stand a serious chance of eventually crippling it, including the state’s defense industries. Pyongyang’s leadership also inadvertently testified to the success of the sanctions campaign — or at least the promise of its success — by ratcheting up its hysterical war rhetoric as the Trump administration rolled out its policies.

Perhaps Richard Nixon’s Vietnam War “madman theory” helps to explain Trump’s initial success: As a new and rather different sort of political leader, Trump could credibly play the part of a madman. From his tweets about “fire and fury” to the “bloody nose” rumor (White House press corps speculation about preemptive U.S. strikes against the DPRK), new uncertainties about the U.S. commander in chief may have helped pull China and other reluctant partners into line.

Also, last month, President Trump announced that the U.S. was withdrawing from its multilateral nuclear deal with Iran. While this decision provoked outcry, exiting the deal was exactly the right move for a “maximum pressure” campaign on North Korea. As the Hudson Institute’s Tod Lindberg noted, an agreement like this — generously front-loaded with benefits, a bit vague about the nonproliferation back end — is exactly what North Korea would demand if the U.S. maintained a similar deal with Iran. But Trump unburdened himself of this potential complication.

As he prepared to head to Singapore for a first-ever face-to-face meeting with Kim Jong-un, Trump looked well positioned to wrest genuine international concessions from a North Korean dictator — something that had arguably never been done before. He was certainly better positioned than any previous president to roll back North Korea’s nuclear clock.

Given the hopes that President Trump’s North Korea policy had generated in the roughly 18 months leading up to Singapore, the results were little short of shocking. There is no way to sugarcoat it: Kim Jong-un and the North Korean side ran the table. After one-on-one talks with their most dangerous American adversary in decades and high-level deliberations with the “hard-line” Trump team, the North walked away with a joint communiqué that read almost as if it had been drafted by the DPRK ministry of foreign affairs.

The dimensions of North Korea’s victory in Singapore only seemed to grow in the following days, with new revelations and declarations by the two sides. What remains unclear at this writing is whether the American side fully comprehends the scale of its losses, and how Washington will eventually try to cope with the setbacks the meeting set in motion.

Kim Jong-un’s first and most obvious victory was the legitimation the summit’s pageantry accorded him and his regime. The Dear Respected Leader was treated as if he were the head of a legitimate state and indeed of a world power rather than the boss of a state-run crime cartel that a U.N. Commission of Inquiry wants to charge with crimes against humanity. In addition to the intrinsic photo-op benefit of a face-to-face with an American president who had traveled halfway across the globe to meet him, the Dear Respected Leader bathed in praise from the leader of the free world: Kim Jong-un was “a talented man who loves his country very much,” “a worthy negotiator,” and a person with whom Trump had “developed a very special bond.” Kim even garnered an invitation to the White House. These incalculably valuable gifts went entirely unreciprocated.

Second: Kim was handed a major victory in terms of what went missing from the summit agenda. For the Kim regime’s security infractions are by no means limited to its domestic nuke and missile projects.

In getting a pass on all these matters in the official record of its deliberations with Washington, North Korea scored a huge plus.

Third: Regarding the key issues that were mentioned in the joint statement, the U.S. ended up adopting North Korean code language.

Until (let’s say) yesterday, the U.S. objective in the North Korean nuclear crisis was to induce the DPRK to dismantle its nuclear armaments and the industrial infrastructure for them. Likewise with long-range missiles. Thus the long-standing U.S. formulation of “CVID”: “complete verifiable irreversible denuclearization.” But because the nuclear quest is central to DPRK strategy and security, the real, existing North Korean state cannot be expected to acquiesce in CVID — ever. Thus its own alternative formulation, with which America concurred in Singapore: “complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.”

In this sly formulation, South Korea would also have to “denuclearize” — even though it possesses no nukes and allows none on its soil. How? By cutting its military ties to its nuclear-armed ally, the U.S. And if one probes the meaning of this formulation further with North Korean interlocutors, one finds that even in this unlikely scenario, the DPRK would treat its “denuclearization” as a question of arms control — as in, if America agrees to drawing down to just 40 nukes, Pyongyang could think about doing the same. The language of “denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula” ensured that no tangible progress on CVID was promised in the joint statement.

Likewise the communiqué’s curious North Korean–style language about agreeing to build a “peace regime” on the Korean Peninsula. What is the difference between a “peace regime” and plain old “peace,” or, say, a peace treaty among all concerned parties? From the North Korean standpoint, a “peace regime” will not be in place until U.S. troops and defense guarantees are gone — and a peace treaty between North and South may not be part of a “peace regime,” either, because that would require the DPRK to recognize the right of the ROK to exist, a proposition it has always rejected.

Fourth: The North delivered absolutely nothing on the American wish list at the summit and offered only the vaguest of indications about any deliverables in the future. No accounting of the current nuke and missile inventory. No accounting of the defense infrastructure currently mass-producing nukes and missiles. No accounting of WMD sales and services in the Middle East, or cyber-crime activities, or counterfeiting, or drug sales. Not even a small goodwill gesture, such as the release of Japanese abductees or an admission that North Korean agents did indeed kidnap David Sneddon, a young American last seen in China, as many who have followed the case believe.

Nor did Team Trump’s much-vaunted timetable for handing over nukes and dismantling WMD facilities emerge. Quite the contrary: As Bruce Klingner of the Heritage Foundation and others have pointed out, the joint language commits North Korea to even less than any of its previous (flagrantly violated) nuclear agreements did: less than its agreements with South Korea in 1991 and 1992; less than its Agreed Framework in 1994; less even than the miserable Joint Statement from the so-called Six-Party Talks in 2005.

With the Singapore communiqué in hand, the Dear Respected could return home and rightly claim that the Americans had not laid a glove on him. The diplomatic debacle for America, on the other hand, only seemed to grow as new details surfaced and new pronouncements about the meeting were issued.

In fairness, we should acknowledge that the Singapore summit may not be quite as awful for the American side as events to date suggest. It is possible, for example, that the U.S. secured meaningful deliverables that have not been publicly announced. But as my American Enterprise Institute colleague Dan Blumenthal has emphasized, the North Korean media would have to ready Kim’s subjects and elite for any concession or change in policy worthy of the name — and there is, as yet, no evidence of this. More likely, alas, is the possibility that Kim and Co. treated the Americans in private to a number of grand and utterly unenforceable promises — North Korean diplomacy specializes in this particular device. Conversely, we do not yet know what the U.S. may have given the North out of public view: The joint statement talks of U.S. “security guarantees” for Pyongyang, for example, but apparently we will learn what this means only in the fullness of time.

At any rate, the public record of the summit looks like a World Series of unforced errors for America, needlessly boxing us into a corner where we should not want to be. In addition to undermining our alliance with South Korea, the summit weakened the rationale for aggressive economic sanctions against the DPRK. After all, if there is no more North Korean nuclear threat, as Trump claims, why should there be “maximum pressure”? Washington asserts that sanctions against North Korea will still be enforced until DPRK denuclearization is completed. But as a practical matter America will find it increasingly difficult to rein in the governments that want to break ranks — most important, China, Russia, and our ally South Korea.

Within hours of the Singapore communiqué, Beijing was already calling for an easing of those sanctions, and reports allege that Beijing has already begun to ease them unilaterally. The more porous the sanctions, the faster North Korea can credibly threaten San Francisco with incineration.

The mystifying question of the Singapore summit is this: How could the American team make so many major-league miscalculations at a single sitting? Why would the president take the lead in subverting his own North Korea policy — the first such policy in a generation to make an inroad against the North Korean threat? A comprehensive assessment must await future historians, but we already have a few clues.

The U.S. position at the summit, to begin, betrayed poor preparation for the negotiations and an almost inexplicable unfamiliarity with the negotiating partner. In the lead-up, for example, the U.S. counted as good-faith gestures North Korea’s decommissioning of a nuke test site at Mt. Mantap that was no longer usable and a special promise to cease nuke and missile tests even though Kim had already declared at the start of the year that the DPRK was moving from testing to mass production and that further testing was not needed for now.

America’s naïveté at the summit was perhaps most vividly and embarrassingly encapsulated by a bizarre movie-trailer-style video from something called “Destiny Pictures” that the U.S. team obliged the Dear Respected Leader to watch: a short film clip fantasizing about the real-estate and technology bonanza a wealthy future North Korea could enjoy if only Pyongyang’s leadership made the decision to give up the nukes and become a peaceful state.

The provenance of this video is unclear — the U.S. National Security Council has formally taken responsibility for it, though some viewers say it practically screams “Made in South Korea” — but regardless, the product itself constituted a painfully poor job of salesmanship. No one who had heard of songbun, the control system that assigns roughly a third of North Korea’s population to a bleak fate in the “hostile classes,” could ever imagine that Kim Jong-un wants all his subjects to be rich. Nor were the producers apparently aware that Kim already has a plan in place for stimulating both national prosperity and military might: It is called byungjin, or “simultaneous pursuit.”

We know, for example, that President Trump made an on-the-spot determination to meet with Kim Jong-un after being briefed in March by the South Korean national-security adviser about Kim’s desire for a U.S.–DPRK summit. By the same token, after President Trump’s decision in late May to call off that summit in response to an especially vicious statement from the North Korean foreign ministry, South Korean president Moon Jae-in immediately held an emergency summit with Kim Jong-un, thereafter coaxing Trump to put the summit back on.

At the end of the day, the incontrovertible fact is that President Trump showed himself to be hungry for this summit, no matter what. Whether President Moon’s flattering comments about the Nobel Peace Prize had any impact on that appetite cannot yet be determined. What is clear is that Team Trump, which had consistently avoided the sorts of mistakes previous administrations had made, stumbled into a series of North Korean negotiating traps. To judge by the evidence at hand, it would appear that the president strongly preferred the prospect of a bad deal with North Korea to no deal at all.

What comes next? Both sides say there will be more U.S.–DPRK conferencing and negotiating; this does indeed look likely. The U.S. says it will firmly maintain “maximum pressure” until North Korea dismantles its nukes; while that is possible, it is not entirely likely.

The U.S. also says it expects the North to begin delivering on meaningful denuclearization by the end of the year. This would have been an unrealistic notion before the Singapore summit, but in the wake of the summit it looks like dreaming. Only if the North Korean regime chooses to chart an entirely new — and from the standpoint of regime stability, extremely dangerous — course could there be hope for what the international community would call a happy conclusion to the North Korean crisis. Thus far there is absolutely no evidence that the Kim regime is even toying with the idea of such a course.

Some prominent voices have averred that North Korean denuclearization would necessarily be a complex and protracted affair. One highly esteemed expert, Siegfried Hecker, has even ventured that the process could take up to a decade and a half to complete. Hecker must not have been involved in the denuclearization of Ukraine at the end of the Cold War. For a time, Ukraine possessed the world’s third-largest nuclear arsenal: roughly 1,800 warheads. In December 1994, Ukraine joined the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. In June 1996, the last nuclear warhead in the Ukrainian arsenal was removed from Ukrainian soil. If Ukraine could denuclearize in a year and a half, the DPRK — with an inventory orders of magnitude smaller — could presumably do so in months. But only if it wanted to. What is lacking for North Korean denuclearization is not technical expertise; it is a desire to disarm.

Having bested the Americans in Singapore, North Korean leaders must be looking forward to repeats and three-peats in upcoming talks. And Pyongyang has already laid down a number of markers for all who are willing to see them.

It is no accident, for example, that the Dear Respected arrived in Singapore in an Air China jet. Beijing is once again very publicly in North Korea’s corner: It will be advocating once more a “freeze for freeze” (a cessation of already-ended DPRK nuke and missile tests in exchange for a halt in joint U.S.–ROK training) and a process of “phased denuclearization,” a term that can best be translated for the non-specialist as “no North Korean denuclearization at all.” No love is lost between Chinese and North Korean leadership, but they are united in the overarching strategic objective of overturning Pax Americana in Asia.

By the same token, barely a week before the Singapore summit, North Korea’s KCNA news service reported that Syrian president Bashar al-Assad was looking forward to arranging a state visit to Pyongyang to parlay with Kim Jong-un. The subtext here is not hard to see: North Korea has a lot of clients who are willing to pay good money for its weapons of mass destruction, and if the Americans want to end these sales, Washington is going to have to pay up instead.

The money matters to Pyongyang. Until the international sanctions are lifted, the Kim regime must draw down its financial and strategic reserves to fund its nuke and missile programs. Nukes and ICBMs are expensive — not least for a technologically backward and financially bankrupt nation with a tiny economy. So long as the sanctions are working, the DPRK is in a race against time; if the sanctions can be broken, North Korea will have the breathing space to get its nuclear game up to the next level, and on a timetable of its own choosing.

As for the United States and her allies, the setback in Singapore was serious but by no means insurmountable. The U.S. still has vast resources — economic, diplomatic, military — that it can deploy. It can progressively reduce the scale and scope of the North Korean threat if it falls back to a Plan B that resembles its Plan A up until about a month ago.

There should be no doubt that Pyongyang will be more confident and assertive after Singapore. The Kim regime is betting that it has already taken the worst the Trump administration has to give. For our own national security, and for that of our allies, we must hope they are wrong.

First published at the National Review

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense