By Dr. Shehab Al‑Makahleh

When undersea telecommunications cables are damaged, investigators instinctively look for ships, anchors, or evidence of sabotage. That script has played out repeatedly in the Baltic Sea, where severed cables and damaged seabed infrastructure—alongside gas pipelines—have triggered vessel inspections and heightened concern over gray‑zone coercion by Russia and China. NATO navies and European security services now treat the seabed as a contested domain, routinely mapped, probed, and occasionally disrupted as part of great‑power competition.

Yet even if every cable on the ocean floor were perfectly guarded, the United States would still face a deeper and more consequential vulnerability. American digital and military power does not hinge solely on physical cables, but on fragile upstream supply chains that quietly determine whether those networks can be built, expanded, or repaired at scale. Among the most overlooked of these chokepoints is germanium.

Germanium is an unglamorous metalloid—atomic number 32 on the periodic table, named after Germany—that rarely makes headlines alongside lithium or rare earths. But it plays a critical role in modern fiber‑optic networks. Germanium compounds are used as dopants to fine‑tune the refractive index of fiber cores, enabling low‑loss, high‑performance data transmission. Without it, the physical backbone of the digital economy—from cloud computing to military command‑and‑control—becomes harder and slower to extend.

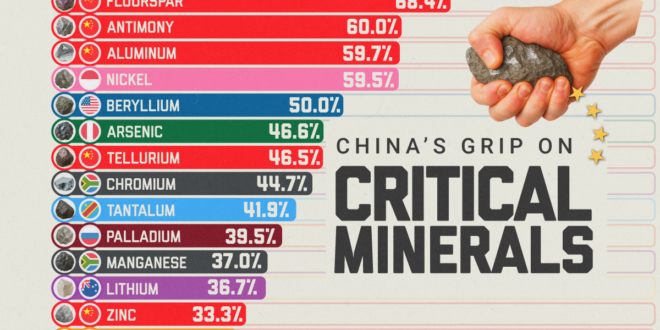

This is where China’s leverage matters more than seabed sabotage. Beijing does not need to cut cables to constrain American power. By shaping access to upstream inputs like germanium through export licensing and regulatory controls, it can introduce delay, uncertainty, and cost into the expansion and repair of the very networks that underpin U.S. economic and military strength.

The Illusion of Physical Security

Western debates about digital vulnerability tend to fixate on visible threats: cyber intrusions, satellite warfare, 5G standards, or the physical security of undersea cables. These are real risks. Fiber‑optic networks carry military command‑and‑control, intelligence traffic, financial clearing, and the data flows that sustain joint all‑domain operations. They even enable the use of unjammable drones in the war in Ukraine.

But these discussions often assume that the physical network is fungible and resilient—that cables can always be replaced, rerouted, or repaired if damaged. This assumption collapses when upstream industrial realities are taken seriously. Fiber networks depend on small, specialized supply chains that are slow to adapt and difficult to surge in a crisis.

Germanium sits at the center of this problem. China has long dominated its refining and processing. Although Beijing eased a full ban on germanium exports in late 2025, licensing and regulatory controls remain. The effect is not a dramatic cutoff, but something more subtle and strategically effective: friction. Delays in approval, higher prices, and uncertainty over future access all slow investment and complicate planning.

The Biden administration has begun to recognize this vulnerability. In January 2026, the White House formally declared processed critical minerals and their derivative products—including germanium—essential to national security and defense‑industrial resilience, directing negotiations with partners to adjust imports accordingly. This is an important step, but it underscores how late the realization has come.

Germanium and the Logic of Chokepoints

Germanium is especially well‑suited to supply‑chain leverage because of how it is produced. It is rarely mined directly. Instead, it is recovered as a byproduct of zinc smelting and other industrial processes. That makes its supply structurally inelastic. Rising prices do not quickly generate new output, because no producer mines zinc simply to harvest germanium on the side.

This market failure locks the supply curve in place. Even dramatic price increases cannot rapidly expand availability. Output is tied to unrelated host‑metal production cycles and to specialized refining capacity that takes years—not months—to build. Money alone cannot solve the problem in the short term.

In fiber‑optic manufacturing, this rigidity becomes operationally binding. Germanium dopants must meet tight purity and performance standards. Substituting alternative materials is technically possible, but slow and expensive due to certification, qualification, and reliability requirements. Small shortfalls can therefore have outsized effects, delaying entire projects or raising costs across civilian and military systems.

The strategic logic is familiar. During World War II, Allied planners targeted German ball‑bearing plants not because they were glamorous, but because they were narrow industrial inputs that constrained the entire war machine. Germanium occupies a similar position in today’s digital infrastructure ecosystem.

Scale, Repair, and Strategic Time

The stakes grow when this chokepoint is viewed against the scale of global fiber expansion. Undersea cable capacity is expected to increase by nearly 50 percent by 2049. The United States is simultaneously pushing for massive fiber build‑outs to support broadband access, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and data‑intensive military operations.

Upstream constraints shape not only how fast new networks can be deployed, but how quickly damaged infrastructure can be repaired and redundancy established after disruption. In a crisis, time matters. A delayed repair is itself a strategic effect.

Some mitigation efforts are underway. In 2025, the Pentagon announced an $18.5 million investment to expand domestic germanium and silicon‑optic production capacity, signaling a shift toward resilience rather than passive dependence. Recycling is emerging as another critical strategy. Recovering germanium from manufacturing scrap and yield losses can reduce exposure to offshore bottlenecks.

Private investment is also moving in this direction. Korea Zinc’s announced $7.4 billion expansion of a Tennessee processing facility—designed to extract value from existing waste metals, including germanium—reflects a growing recognition that supply‑chain security is as much about reuse and processing as it is about new mining.

The Quiet Geography of Power

The broader lesson is sobering. Infrastructure systems that appear robust often rest on narrow upstream foundations that quietly determine their resilience. In modern competition, an adversary does not need to trigger a crisis or visibly attack infrastructure to gain leverage. It can shape the political economy of inputs that govern timing, cost, and adaptability.

As seabed warfare and supply‑chain statecraft become normalized features of great‑power rivalry, controlling what builds critical infrastructure may prove just as consequential as controlling the infrastructure itself. The future of American digital power will be decided not only on the ocean floor, but in smelters, refineries, and licensing offices far upstream.

Ignoring that reality risks defending cables while surrendering the materials that make them possible.

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense