The character of warfare has changed over millennia, but it has always remained a fundamentally human endeavor. What will happen when artificial intelligence commands it?

The Department of the Air Force (DAF) believes the nature of war—not just its outward, superficial character—is about to metamorphose beyond recognition.

The framers of a December 2024 report to Congress titled “The Department of the Air Force in 2050” stop short of issuing such a stark verdict. But it’s hard to come away from the report, which bears the seal of approval from former Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall, without inferring that the next twenty-five years portend change of world-historical import—not just for the U.S. Air Force and Space Force, but for the U.S. joint force and armed services across the globe.

Read the whole thing. It is 22 pages long, and amply repays the investment of time.

If the DAF team calls it right—and they concede that we can only glimpse the future dimly—warfare stands at the brink of becoming a contest between machines rather than between human warriors who flourish machines such as planes and ships, missiles and bombs as weapons. They maintain that artificial intelligence, autonomous systems, and other novel technologies are merging into a mode of warmaking so protean and fast-paced that no human decision-maker could possibly keep up. Only artificial intelligence, they say, will be able to observe the operational and tactical surroundings, orient to transients as the antagonist adapts its tactics, decide how to reply to new conditions, and act in an effort to attain victory.

And then repeat.

Colonel John Boyd’s renowned “OODA” cycle—observe, orient, decide, act—will blur past human comprehension. Opines the report: “We are evolving toward a remote-control war which, by 2050, may be a reality.” For its coauthors, then, this is a question of when—not if. Best to start preparing now. “Success in this type of conflict,” it goes on, “will require a blend of advanced sensors, other information sources, secure communications, and state of the art AI to support decision making.” And tomorrow will demand a very different U.S. Air Force and Space Force from today’s.

In other words, the human factor in armed strife may soon suffer a drastic downgrade. If human choice and appetites fade, the nature of war will indeed have changed.

The Nature of War Has Never Changed—Until Now

Now, the character of war is constantly in flux. It always has been, and always will be. Methods of fighting change along with changing times, circumstances, and technology. For millennia, by contrast, standard wisdom, including from yours truly, has held that the nature of war is eternal and unchanging.

That’s why we study military history. We believe this has all happened before, and will happen again. So we can derive insights of enduring worth from reviewing what past combatants did right, wrong, or indifferently.

That’s why tomorrow’s decision-makers will still profit from reading Thucydides’ classic History of the Peloponnesian War, well over two millennia after the Athenian soldier-historian penned it. Thucydides depicts his chronicle of the system-shattering war between Athens and Sparta as a “possession for all time.”

That’s more than braggadocio. If, at bottom, war is an interactive clash of human wills between contenders who deploy violent force to coerce one another into submission, then the Peloponnesian War—a trial of arms in which armies wielded spears and rowed warships constituted the coin of the realm for navies—remains as relevant in the twenty-first century, an age of precision-guided arms, as it was in Greek antiquity.

The basics of war are everlasting. Only the fighting implements change. Or so we thought.

What Happens When War is No Longer Human?

Now think about what remote-control warfare would mean in Clausewitzian terms. Like Thucydides, Carl von Clausewitz, the martial sage of Prussia, regards war as a thoroughly human endeavor and sees the same patterns recurring again and again in military history. To navigate complexity and chaos, Clausewitz entreats commanders and their political masters to keep calm and carry on—doing their utmost to remain rational amid the clangor of combat, an arena inimical to rational thought and deed.

Clausewitz observes that remaining levelheaded is far from easy. That’s why he belabors his point. Dark passions such as hatred, rage, and spite, not to mention the fog and friction that pervade any battleground, have a way of deflecting warmaking from the path that pure cost-benefit calculations might chart.

But that observation might be moot by 2050. Turning warfare over to machines—contrivances that are dispassionate by definition—would reduce the element of human passion in warfare, if not eliminate it altogether.

Game-changer is a cliché in military circles, but it fits in this case. Not just the rules, but the very essence of the game, verge on fundamental change if the DAF report calls the trendlines right.

And what about military leadership? Sun Tzu, ancient China’s soldier-scribe of lasting fame, depicts the general’s virtue—a human quality—as one of just five core elements of any martial encounter, alongside weather, terrain, command, and doctrine. In a similar vein, Clausewitz writes of the “military genius,” the supreme commander gifted with an “inward eye” for peering through the fog of war and discerning what to do amid chaos, and the “inward fire” to rally the army to do it.

Leadership is a human art and science.

But as we approach 2050, perhaps such leadership will be less and less necessary. AI-driven engines of war will boast unprecedented capacity to gather, evaluate, and harness data about the operating environment—clearing the fog of war, at least in part. (Of course, machine combatants will doubtless try to deceive and perplex one another. The fog will never lift completely.) Nor will machine warriors know passion or morale, obviating the need for inspirational leadership. In short, the battlefield of 2050 could annul much of what Clausewitz and fellow military thinkers wrote about the “climate” of war.

To what result remains opaque. Kendall & Co. espy a brave new world taking shape.

America Will Be Vulnerable

There’s a coda to the report, one that applies specifically to North America. The coauthors foresee the United States’ fortunate geographic position coming to an end, at least in part. No, invading hordes will not be swarming ashore in Boston or Los Angeles. The nation’s oceanic ramparts endure. But the advent of ultra-long-range precision ordnance means that conventional strikes on the homeland are virtually certain in times of conflict. The DAF team notes that such armaments—ballistic missiles, hypersonics, orbital bombardment systems, and the like—can be “launched from any domain,” while prophesying that there will be “no sanctuary from these weapons.”

Battlefield America.

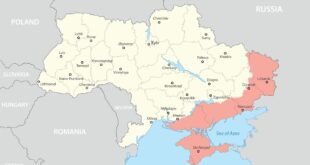

In one sense, this is nothing new. The homeland has been vulnerable to attack across the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic since the dawn of the atomic age. Nevertheless, technological advances mark a departure from the arcane realm of mutual assured destruction. Contemplating nuclear warfare means thinking about the unthinkable. But conventional strikes come without radiation, electromagnetic pulses, and other ghastly nuclear effects. Raining non-nuclear munitions against an enemy’s homeland is extremely thinkable—as the Russia-Ukraine war has demonstrated many times over.

There is little reason to think a foe would exempt America from similar rough treatment in times of war.

In fact, red-team magnates would likely view asymmetric strikes as an obvious choice. Hostile commanders could hope to exact disproportionate psychological impact from bombarding the U.S. homeland. Generations of Americans have grown unaccustomed to thinking of North America as strategic ground. That’s because it hasn’t been for a long time. The last time a foreign assailant actually invaded the United States was during the War of 1812, which wrapped up 210 years ago. After such a lapse, strikes in the country’s midst could disorient the populace to an opponent’s strategic gain.

The public frenzy that greeted the Chinese spy balloon that wafted across the country in 2023 could beguile the Beijings and Moscows of the world into action. Here, too, it seems a brave new world is almost upon us.

“The Department of the Air Force in 2050” leaves military and diplomatic folk with potentially seismic shifts in human affairs to ponder. So let’s start pondering. Forewarned is forearmed.

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense