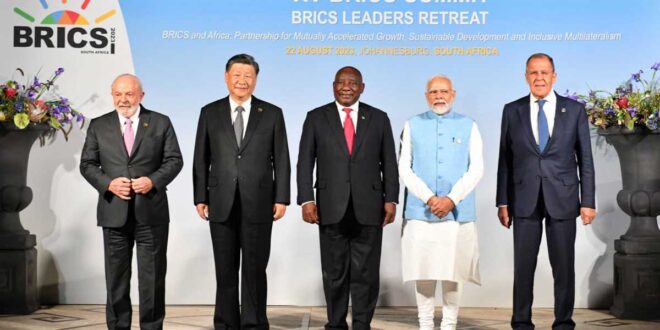

It has been a year since the announcement of the enlargement of the now-recognized BRICS Plus, which saw Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates all adhered to the group, collectively representing over 30 percent of the global GDP and nearly half of the world’s population. However, the group’s progress has been uneven, characterized by peaks and troughs. Since its establishment in 2009 and inclusion of South Africa in 2011 – which raised expectations for more pluralist representation – BRICS has made significant strides, such as establishing financial institutions in 2014, promising alternative financing options outside the value-deterministic frameworks of the IMF and World Bank. However, progress has nearly stagnated due to geopolitical tensions spanning from the Asia-Pacific to the doorstep of Europe. Furthermore, intra-BRICS issues have been simmering for over a decade, limiting the bloc’s ability to reach a consensus and, at times, even threatening the risk of fragmentation.

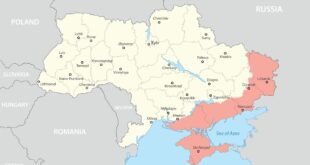

For one, China’s efforts to assert centrality within the bloc have been met with apprehension by India. Similarly, the institutional initiatives of China, Russia, and India have often clashed due to overlapping geopolitical spheres of influence. More critically, the Sino-US Trade War and their competition for influence in the Asia-Pacific, and Washington’s support for Ukraine in response to Russian military adventurism have taken precedence on their respective agendas. Similarly, questions about BRICS’s trajectory following its expansion have emerged, as some of the new members appear to contribute more to the group’s role as a “political asset of strategic value” in countering US hegemony, rather than supporting its original proposal for reforming the global finance and governance architectures. These developments have often strained the group, consuming significant politico-economic resources that could otherwise be directed towards advancing changes aligned with collective interests.

Despite the status discrepancy, diverse interests, and uncertainties about the bloc’s future, BRICS has continued to expand. This reveals a discernable pattern that has marked the group’s key milestones: Brazil’s persistent political efforts to develop and strengthen BRICS, particularly under President Lula’s left-wing Workers Party administrations. Thus, it is essential to clarify the connection between Brazil’s foreign policy tradition and the various pathways it pursues to achieve international status.

Under the administrations of both Lula (2003-2010, 2023-Current), and Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016), an economically rising Brazil led various global governance initiatives aimed at expanding and solidifying its regional and international status. During this period, BRICS built upon the successes of the IBSA forum (India-Brazil-South Africa), eventually leading to the establishment of the New Development Bank in 2014, where Rousseff currently serves as President. In contrast, former presidents Michel Temer (2016-2018), from the center-right wing Democratic Brazilian Movement party, and Jair Bolsonaro (2019-2022), from the center-right parties Social Liberal Party and later Liberal Party – both of which adopted more conservative positions during his tenure – pursued a strategic shift towards the US and the West. Specifically, Temer prioritized Brazil’s candidacy for ascension to the OECD, while Bolsonaro, who shared various ideological traits with former US President Donald Trump – including a dismissive attitude towards international institutions – displayed a lack of fanfare for the BRICS. These contradictory approaches are fundamentally rooted in Brazil’s foreign policy tradition, which has historically been characterized by two paradigms:

First, the Americanism paradigm posits that status is achieved by reinforcing US hegemony in the Western hemisphere and beyond, based on ideological affinities and US-led Pan-Americanism doctrines. This approach was notably orchestrated by Brazil’s most prominent diplomat, the Baron of Rio Branco, in the early 20th Century, as he pragmatically sought US support to set Brazil’s border disputes. Similarly, Oswaldo Aranha, Brazil’s Ambassador to the US, advocated for a Brazil-US alliance during World War II to guarantee economic and security benefits. During the Cold War, President General Castello Branco’s Minister of Foreign Affairs famously stated, “What is good for the United States is good for Brazil”, reflecting a desire for automatic alignment that was evident in Brazil’s brief involvement in the US-led military intervention in the Dominic Republic in 1965. Most recently, this paradigm regained momentum under Bolsonaro’s efforts to closely align with Washington during Trump’s presidency, culminating in Brazil’s designation as a major non-NATO ally.

Second, Globalism (or Universalism) presents a counter-narrative to Americanism. While Americanism advocates for supporting US hegemony, Globalism calls for Brazil’s autonomy in foreign affairs by reducing its dependency on the US and the West. Crucially, this paradigm recognizes that Brazil’s pursuit of status requires international support, which can be achieved through the pluralization of pragmatic partnerships and the promotion of alternative, non-Western-centric frameworks. For instance, President Jânio Quadro’s independent foreign policy in 1961 included the resumption of diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union (1961), criticism of the US-led OAS’ decision to expel Cuba, and a prioritization of ties with Africa. It was later reassessed by the presidents of the military regime following Branco, especially Ernesto Geisel, who advocated for “inclusive and responsible pragmatism” by re-engaging with communist states such as China and Angola, and promoting a “third way” beyond the US-USSR bipolarity. Most recently, Lula’s conception of “autonomy through diversification” has emerged as the most sophisticated form of this foreign policy paradigm. In this approach, Brazil aims to assume a leadership role for the developing world by expanding partnerships with peripheral states and rising economies, thereby enhancing its status as representative of the developing world.

These considerations demonstrate that if Brazil seeks to pursue a rising power status independent of the US influence, it has limited options other than fostering Global-South platforms such as the BRICS, CELAC, and UNASUR as its primary modus operandi. Essentially, its export portfolio, characterized by a high economic dependency on commodities, its slow-paced industrialization when compared to other top-ten ranked economies, and its limited defense capabilities hinder its ability to pursue great power status in its traditional form. Consequently, if Brazil aims to increase its global footprint and to foster its envisioned new international order – characterized as “multilateral and less asymmetric, and free of hegemonies” – it may need to rely primarily on other nations to follow its example as a responsible rising power, given its lacks of coercive capabilities to unilaterally advance its agenda. Brazil’s achievements under Lula’s first two terms – such as collective action against protectionist measures during the Doha Round at the WTO and reforms of the IMF voting quotas – illustrate its reliance on intensified political coordination to address its interests. However, these approaches do not grant Brazil centrality, as concessions must be made to secure international support. Similarly, Brazil’s advocacy for changes in international structures and pro-multipolarity rhetoric are executed with caution, as Lula frequently reassures that the BRICS does not seek to “counterpoint the United States”, aiming to avoid political friction with Washington.

Despite facing politico-economic challenges, including increased domestic political polarization, Lula has still managed to mobilize sufficient political action and allocate resources to fulfill the “Brazil is Back”promise of his third mandate. Particularly, Brazil’s presidency of the 2024 G20–marked by the historical participation of the African Union as a new member bloc–and its hosting of the 2025 COP present significant opportunities for Lula to promote his vision for the international system and garner support for his pro-multipolarity agenda. However, although more than 40 states have expressed interest in joining the group, including Cuba, Kazakhstan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Algeria, the next expansion may be delayed by at least another year due to Russia’s temporary suspension of new memberships. Finally, as Brazil prepares to hold the BRICS presidency in 2025, Lula may size the momentum to resume the inclusion of some of the “Friend of BRICS” in pursuit of “building a multipolar, fair and inclusive order”.

Nevertheless, such trajectories must be pitted against the argument that BRICS expansion may not deliver the anticipated benefits for Brazil. Notably, the inclusion of new members on equal terms with the original five could dilute Brazil’s influence within the group, weakening its ability to shape its agenda. Furthermore, considering the informal natural of BRICS – lacking the structured voting mechanisms typical of formal international organizations – decision-making could be more complex and cumbersome as the group expands, making consensus more difficult to achieve with a larger and more diverse membership. In turn, the likelihood of these arise of heterogenous goals could be a potential weakness, undermining expectations for the establishment of a new global order, a common desire of many within the group.

For instance, Brazilian diplomat Paulo Roberto de Almeida likened Brazil’s involvement in BRICS to a “ball and chain,” cautioning that it could become deeply entangle in the groups’ expansion, which he views as driven by China and Russia’s great power ambitions. He argued that this entanglement could prove “potentially prejudicial” by significantly undermining Brazil’s “traditional autonomy and independency on foreign affairs.” This suggests the presence of divergent strategic priorities within Brazil foreign policy trajectories, which, while they may initially appear as lack of unified strategic goal, actually underscore Brazil’s flexible and context-sensitive approach to international issues. Rather than adhering strictly to a single paradigm, foreign policy decisions are shaped by day-to-day assessment on how to best advance national interests, grounded on a dynamic evaluation of risks and opportunities and, more crucially, often subjected to the domestic political pressures and constrains. As a result, shifts in political leadership, particularly when there are stark ideological differences, are expected to produce significant shifts in a state’s foreign policy trajectory and strategic priorities. In this context, as the future administrations may adopt the Americanist policy paradigm and deprioritize BRICS in favor of the alternative approach to pursuing the national interests, the groups informality – lacking biding enforcement and compliance mechanisms – could be considered an advantage for Brazil, allowing for greater flexibility in adjusting its level of engagement without facing formal constraints or obligations.

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense