“The concern is is this going to cause an escalation because in downtown Beirut they took somebody out, and in downtown Tehran they took someone out,” Reed said. “The question is what effect will it have on negotiations. I don’t think it will help it, I think it will set it back. That might be part of the logic of the attack on him too.”

Without some sort of truce, U.S. officials fear Israel and Hamas will ratchet up the violence, with Israel in particular deciding that the only way to eventually calm Gaza is through more fighting now.

That could lead to escalation by other groups that are already exchanging fire with Israel, including Hezbollah and the Houthis in Yemen, and pull the whole region into a conflagration. In particular, it could lead to direct battles between Israel and Iran.

In the months since Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel, which killed some 1,200 people, Israel has fought the Palestinian militants but also engaged in multiple rounds of talks with them about temporary truces and hostage releases, including one major successful effort.

The violence between Israel and Iran-backed Hezbollah forces in Lebanon has reached new heights in recent months, but the U.S. has pursued indirect talks on that front as well. That’s even though American officials believe that Hezbollah won’t back down in its faceoff with Israel until after Hamas agrees to a cease-fire with the Israelis.

An alleged Hezbollah strike that killed a dozen children at a soccer field in the Golan Heights has thrown a wrench on every front. That attack — which Hezbollah denied responsibility for — is what is thought to have led Israel to carry out the strike in Beirut against Shukr.

The U.S. perceived the strike in the Lebanese capital as a standard, proportional response for the killing of the children, according to two U.S. officials, although it was unclear how Hezbollah would respond. Like others, the officials were granted anonymity to discuss sensitive issues.

The attack in Iran could have far larger implications.

The White House did not receive a heads-up about it, one of the officials said. Blinken appeared to confirm this, saying, “this is something we were not aware of or involved in.” Israel has stayed silent on the strike, but U.S. officials have not yet received information that would suggest another player carried it out.

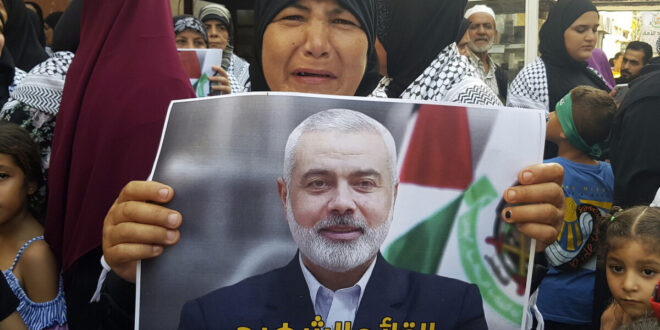

One obvious question is why Israel would take out Haniyeh now.

The assassination of the Hamas political leader will make intermediaries and hosts of Hamas feel “a bit like the rug is being pulled out from under them,” said Nathan Brown, a George Washington University professor who previously served as an adviser for the committee drafting the Palestinian constitution.

Israel still wants to move forward with a cease-fire deal with Hamas in the coming weeks, according to an Israeli official. The official added, however, that the momentum Israel and the U.S. gained at the beginning of July, when Hamas signaled it was ready to work toward finalizing a deal, has fallen off.

By mid-July, both sides were asking for additional concessions. The Israelis wanted to increase the number of live hostages that would be released under the pact. Hamas wanted Israel to agree to withdraw all of its forces from Gaza, not just from certain populated areas. The negotiating team met again in Rome last week, but did not make significant progress. More talks are expected this week, the senior administration official said.

While Israel stands by its public statements that it does not want to go to war with Iran, it sees the situation with Hezbollah — one of Iran’s most powerful proxies in the region — as one that will only continue to escalate. Israelis have been left feeling that the Shiite militia had “really crossed the line” with its strike that killed the children, the Israeli official said.

“You have a situation where each of the parties believes that in order to deter the other, they have to climb the ladder. And so where we are today with Hezbollah is a different place then where we were … six months ago,” the Israeli official said.

That sentiment matches some analysts’ observations that Israel may be operating on the theory that the best way to get Hamas and Hezbollah to back down and agree to pause hostilities is to demonstrate its strength.

This tactic is often called “escalate to deescalate.”

“Israel is saying by these strikes: We’d prefer to wind all this down diplomatically but if we cannot achieve our goals that way, we will escalate as we would prevail — and that you know we would,” said James Jeffrey, a former U.S. ambassador to Iraq, Turkey and Albania.

Netanyahu also has personal reasons to drag out the fighting.

The Israeli leader is under pressure from far-right figures critical to sustaining his governing coalition not to cede an inch to Hamas and to be more defiant against the Islamist regime in Tehran. Many U.S. officials also suspect that Netanyahu — who is facing corruption charges — feels that continuing the fighting is the best way for him to stay in power and out of jail.

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense