Giancarlo Elia Valori

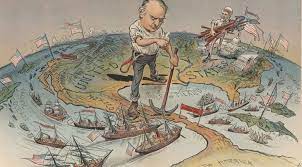

The recent discussions on the Monroe Doctrine in European and US academic circles and in the media have mainly focused on George W. Bush’s and Trump’s Administrations.

Although both Administrations were ruled by the Republican Party, foreign policy often conflicted. In the English-speaking world most of the discussions about the Monroe Doctrine during the era of these two Presidents are related to Latin America. The foreign policy concepts of former Presidents Bush and Trump were very different: the former was characterized by “globalism” and wanted to export the US political system and ideology everywhere by any means. In their policies towards Latin America, however, both regarded it as their exclusive sphere of influence: the Bush Administration supported the Venezuelan opposition to launch a coup to overthrow President Chavez and wage the war on terror in Latin America against countries that opposed US hegemony. The Trump Administration did so even more by flaunting the Monroe Doctrine; encouraging the opposition in Venezuela and Bolivia; by pushing for a regime change in Cuba; by restricting Mexico’s right to free trade and so on. The same holds true for the current Democratic Party’s Administration.

Let us go back in time: in 1933, faced with the growing anti-US sentiment in Latin America, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt announced a “good neighbourhood policy” to counterbalance the influence of Germany and Italy. Nevertheless, this did not mean renouncing intervention in Latin America, but restricting it to non-military methods and attracting more regional allies in the peaceful infiltration action.

Likewise, the Obama Administration’s rise to power in 2009 sought to undermine Bush’s “unilateralism”. In 2013 President Obama’s Secretary of State, John Kerry, stated that the era of the Monroe Doctrine was over but, faced with a series of leftist regimes in Latin America, the United States just replaced the obvious subversive means with more subtle ones: financing NGOs; buying off opposition and manipulating social networks – all this to wage an information warfare, hire mercenaries and carry out targeted eliminations through the “anti-corruption” action manipulated by the aforementioned opposition, etc. And even continue economic sanctions against Cuba.

During the election campaign, even the current Biden Administration said it wanted to follow the outgoing President’s path of “unilateralism”, but internal political constraints have limited the rare political moves that really tried to do so at least with a cosmetic exercise. The United States keeps on imposing sanctions on Cuba and still supports the Venezuelan opposition and restricts free trade rights in Mexico.

The aforementioned duality of the Monroe Doctrine in the United States can be linked to Carl Schmitt’s criticism on the double standard followed by the United States after the Second World War. To this end, the United States recruited the new Cold War accomplices, i.e. the former enemies, Germany and Japan, to build the American Century in an anti-Soviet function. And the former enemies worked well.

The new doctrine for dealing with the former enemies was nothing more than a transposition of the expanded Monroe Doctrine, and hinged around the “right” of appropriation of the world’s raw materials, particularly energy, through conventional wars of aggression, supported by the US public that was traditionally reluctant to intervene in wars for alleged human rights disguising a desire for hegemony.

It is not for nothing that some scholars claim that in the Cold War Germany and Japan can be classified as the new Monroe Doctrine of American universalism – i.e- a shift to the west of NATO, up to the borders of the Warsaw Pact, and to the east, thus being an anti-Sino-Soviet rampart in the Far East. Hence the relationship between capitalist development and the expansion of the Monroe Doctrine into global interventionism.

In Der Begriff des Politischen (The Concept of the Political, 1932) Schmitt pointed out that “politics” is not related to the fields of society, economics and culture. It is a parallel “self”’ that, reaching a certain degree of intensity, determines the distinction between friends and foes, regardless of the commonality of ethical, religious or economic values. Schmitt does not seek to fundamentally reflect on the logic of capitalism itself, but rather criticises its political manifestation that developed to the stage of imperialism regardless of the cultural context in which it was born.

While analysing the Asian policy of Japan’s Monroe Doctrine prior to World War II, we can infer the process changing Japanese perceptions of the Monroe Doctrine among the various political and cultural elites in China. At the beginning of contemporary history – usually set as from 1900 – the Chinese empire became a semi-colony dominated by Japan and the Western powers. From the late Qing dynasty to the Republic of China, from Adm. Li Hongzhang, from Foreign Minister and Prime Minister in pectore, Wu Tingfang, and from Gen. Jiang Jieshi [Chiang Kai-shek] onwards, the basic awareness of many political elites was that China’s territorial integrity depended on the balance of power.

After the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), many Chinese expected – or rather deluded themselves – that Japan would play the role of holding back the European powers. On the contrary, especially as from 1897, the aggression of the European powers in East Asia suddenly intensified. Russia occupied Lushunkuo [Port Arthur, 1898; to Japan from 1904 to 1945]; Germany Qingdao [Tsingtao, 1914], the United Kingdom Weihaiwei [1898-1930] and the United States had already expanded its Monroe Doctrine by creating the Hispanic-American War from scratch (1898) and occupying the Philippines as a window on China.

From 1904 to 1905, the Russo-Japanese War was fought on Chinese soil and a large number of China’s intellectual elites rejoiced over the Japanese victory. It was in that international situation that the vulgate of Japan’s ‘Asianism’ – “Asia for the Asians”, echoing the Monroe Doctrine – provided an apparent temporary collective identity between the two Asian giants.

That situation changed as the main reason was the gradual imbalance in China’s balance of power. Especially during World War I, the European powers – distracted by the unfolding events – reduced their investment of resources, and hence of vital interests, in China. As a result, Japan’s influence suddenly increased and in January 1915 Japan imposed the well-known Twenty-One Demands on China. They were a set of claims made by the Japanese government to special privileges during World War I and would greatly expand Japanese control of China. Japan would retain the former areas that Germany had conquered at the beginning of the war in 1914. It would be strengthened in Manchuria and Southern Mongolia and would play a larger role in railways. The most extreme demands would give Japan a decisive voice in financial, police and government affairs. The last part of them would make China a protectorate of the Rising Sun, thus reducing Western influence. Great Britain and Japan had had a military alliance since 1902 and in 1914 the former asked Japan to enter the war. China published the secret demands and appealed to the United States and Britain. In the final agreement of 1916, Japan relinquished its request for a protectorate, but the Chinese situation remained very severe.

The “May Fourth Movement” of 1919 was, to some extent, a joint anti-imperialist effort made by various factions in China. It grew out of student protests in Beijing on that day. Students gathered in Tiananmen Square to protest against the Chinese government’s weak response to the Treaty of Versailles decision to allow Japan to retain territories in Shandong that had been surrendered to Germany after the siege of Qingdao in 1914. The demonstrations sparked nationwide protests and spurred an upsurge in Chinese nationalism, a shift towards political mobilisation away from traditional intellectual and political elites.

The change in the Chinese elites’ attitude is therefore mainly related to the growth of Japanese power in China. Japan was previously weak; it spoke of an “Asian’ identity and opposed China’s partition by the European powers. But it later strengthened and its behaviour made it clear that it was not fundamentally different from the European powers. It was the essence of Japan’s “Asian Monroe Doctrine”.

It was the writer, journalist and philosopher Liang Qichao (1873-1929) who made the Monroe Doctrine known to the Chinese, besides the visibility of the storytelling brought by American propaganda in the Chinese public during the First World War. After the launch of the CPC-Guomindang cooperation, the Monroe Doctrine became – in most cases – a term with a negative connotation, which meant engaging in a closed circle and not focusing on the overall situation. In the CPC, the Monroe Doctrine was rather studied and discussed to illustrate international affairs, and it was not dealt with within the CPC.

After all, the guerrilla and mobile warfare across borders carried out by the CPC and the National Liberation Army was in itself a way to overcome the Monroe Doctrine, which was typical of warlords in their own territories and areas of influence.

On October 6, 1958, Chairman Mao drafted the Letter to Taiwanese Compatriots (then signed by the Defence Minister, Peng Dehuai), attacking the US military presence in the Western Pacific [from China’s geographical perspective, i.e. the Pacific Ocean that washed the People’s Republic of China]:

“Why did an Eastern Pacific country come to the Western Pacific? The Western Pacific is the Western Pacific people’s Western Pacific, just the same as the Eastern Pacific is the Eastern Pacific people’s Eastern Pacific; this is just common sense, and the United States ought to understand it. There is no war between the People’s Republic of China and the United States; so there is no so-called ceasefire. To talk about a ceasefire where there is no fire, is not it plain nonsense?”

The statement stressed only the regional autonomy of the People’s Republic of China in the Western Pacific and indicated that the United States should not interfere in the affairs of that sea. It did not state, however, that the People’s Republic of China played, or should play, a major role in that sea at all times.

After all, as early as the first cooperation between the CPC and the Guomindang, Chairman Mao only used the term Monroe Doctrine at the “supranational” level. In 1940, in his report The Current Situation and Party Policy, he commented:

“The United States is the Monroe Doctrine plus cosmopolitanism: “Mine is mine, yours is mine”. The United States is not ready to give up its interests in the Atlantic and the Pacific”.

Since the United States was too hands-off, it was easy to offend other powers. Hence, at that time, the People’s Republic of China could take advantage of the contradictions between the imperialist countries, and the Three Worlds Theory was preparing to travel in that direction – i.e. as the ultimate and utmost opponent of the Monroe Doctrine.

Today the contrasts between the People’s Republic of China and the United States in those waters are nothing new, but should be interpreted in history as clashes of opposed geopolitical visions, where the former appeals to international law, while the latter tries to tear it down after the fall of the Pauline katechon, i.e. the Soviet Union.

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense