Giancarlo Elia Valori

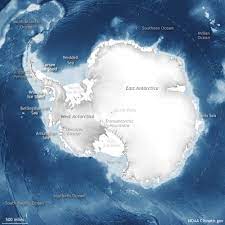

December 1, 2019 marked the 60th anniversary of the signing in Washington of the Antarctic Treaty, the main legal instrument for managing practical activities and regulating interstate relations in the territory 60° parallel South.

On May 2, 1958, the U.S. State Department sent invitations to the governments of Australia, Argentina, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, Great Britain, New Zealand, Norway, the then South African Union and the USSR for the International Antarctic Conference. It was proposed to convene it in Washington in 1959. The group of participants at the Conference was limited to the countries that had carried out Antarctic projects as part of the International Geophysical Year (IGY) (July 1957-December 1958).

The Soviet Union supported the idea of convening a Conference. In a letter of reply, the Kremlin stressed that the outcome of the Conference should be the International Treaty on Antarctica with the following basic principles: peaceful use of Antarctica with a total ban on military activities in the region and freedom of scientific research and exchange of information between the Parties to the Treaty.

The Soviet government also proposed expanding the group of participants at the Conference to include all parties interested in the issue.

In those years, the international legal resolution of the Antarctic problem had become an urgent task. In the first half of the 20th century, territorial claims to Antarctica had been expressed by Australia, Argentina, Chile, France, Great Britain, New Zealand and Norway.

In response to the Soviet proposal, the United States kept all the territorial claims of various countries on the agenda, but it undertook to freeze them. Russia, however, believed that third parties’ territorial claims had to be denied. At the same time, the position of both States coincided almost entirely insofar as the right to make territorial claims for the ownership of the entire continent could be retained only as pioneers.

The USSR relied on the findings of the expedition by Russian Admiral F. G. Th. von Bellingshausen and his compatriot Captain M. P. Lazarev on the sloops-of-war Vostok and Mirnyj in 1819-1821, while the United States relied on the explorations of N. B. Palmer’s expedition on the sloop Hero in 1820.

The Conference opened on October 15, 1959 in Washington DC. It was attended by delegations from twelve countries that had carried out studies as part of IGY’s programmes in Antarctica.

The Conference ended on December 1, 1959 with the signing of the Antarctic Treaty. This is the main international law instrument governing the planet’s Southern polar region.

The basic principles of the Treaty are the following: peaceful use of the region, as well as broad support for international cooperation and freedom of scientific research. Antarctica has been declared a nuclear-free zone. Previously announced territorial claims in Antarctica have been maintained but frozen and no new territorial claims are to be accepted. The principle of freedom to exchange information and the possibility to inspect the activities of the Parties to the Antarctic Treaty have been proclaimed. The agreement is open to accession by any UN Member State and has no period of validity.

Over time, it has been proposed that the political and legal principles of the Treaty be further developed in the framework of regularly convened consultative meetings. Decisions at these meetings can only be taken by the Parties to the Treaty that have a permanent expedition station in Antarctica.

All decisions are taken exclusively by consensus, in the absence of reasoned objections. The first Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting was held in the Australian capital, Canberra, from 10 to 24 July 1961.

Until 1994 (when the 18th Consultative Meeting was held in Kyoto), meetings were held every one or two years, but since the 19th Meeting held in Seoul in 1995 they have begun to be convened on a yearly basis. The most recent Meeting, the 42nd one, was held in Prague from 11 to 19 July 2019. The 43rd Consultative Meeting will be hosted in Paris on 14-24 June, 2021: the suspension of the Meeting that was to be held in Helsinki from 24 May to 5 June 2020 was due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The 17th Meeting was held in Venice, Italy, on November 11-20, 1992.

The main decisions of the Meetings until 1995 were called recommendations and since 1996 ATCM measures. They come into force following the ratification procedure by the Consultative Parties. A total of 198 recommendations and 194 measures have been adopted.

Over sixty years, the number of Parties to the Antarctic Treaty has increased from twelve founders in 1959 to 54 in 2019. These include 29 countries in Europe, nine in Asia, eight in South America, four in North and Central America, three in Oceania and one in Africa.

The number of Consultative Parties to the Treaty that have national expeditions in Antarctica keeps on growing: Australia, Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Chile, the People’s Republic of China, (South) Korea, Ecuador, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, Great Britain, India, Italy, Norway, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Peru, Poland, Russia, Spain, South Africa, Sweden, Ukraine, Uruguay and the United States of America.

The remaining 25 Antarctic Treaty countries with Non-Consultative Party status are invited to attend relevant meetings, but are not included in the decision-making process.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the desire to join the Treaty was reinforced by the desire of many countries to develop Antarctica’s biological and mineral resources. Growing practical interest in Antarctica and its resources led to the need to adopt additional environmental documents.

During that period, recommendations for the protection of Antarctica’s nature were adopted almost every year at the Consultative Meetings. They served as starting material for the creation of three Conventions, which protect the natural environment: 1) the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals; 2) the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources; and 3) the Convention for the Regulation of Antarctic Mineral Resources.

Later, based on the recommendations and Conventions adopted, the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty was drafted. It became an environmental part of the Treaty and was signed on October 4, 1991 for a period of 50 years at the Madrid Consultative Meeting – hence it is also called the Madrid Protocol.

According to the Protocol, Antarctica is declared a “natural reserve for peace and science” and should be preserved for future generations. After 1991, the new countries that adhered to the Treaty started to show interest in participating in large-scale international research projects on global climate change and environmental protection.

Considering the above, Antarctica can be described as a global scientific laboratory: there are about 77 stations on the continent, which have supplied their scientists from 29 countries. They explore the continent itself, the patterns of climate change on Earth and the space itself.

However, how did it happen that the territories of the sixth continent became the target of scientists from all over the world?

In 1908, Great Britain announced that Graham Land (the Antarctic peninsula south of Ushuaia) and several islands around Antarctica were under the authority of the Governor of the Falkland/Malvinas Islands (claimed by Argentina). The reason for this was that they were/are close to the archipelago.

Furthermore, Great Britain and the United States preferred not to acknowledge that Antarctica had been discovered by the Russian explorers Bellingshausen and Lazarev. According to their version, the discoverer of the continent was James Cook, who saw the impenetrable sea ice of Antarctica, but at the same time confidently insisted that there was no continent south of the Earth.

A dozen years later, the appetites of the British Empire grew and in 1917 it decided to seize a large sector of Antarctica between 20° and 80° meridian West as far as the South Pole. Six years later, Great Britain added to its ‘possessions’ the territory between 150° meridian East and 160° meridian West, discovered in 1841 by the explorer Capt. J.C. Ross, and assigned it to the administration of its New Zealand’s colony.

The British Dominion of Australia received a “plot of land” between 44° and 160° meridian East in 1933. In turn, France claimed its rights to the area between 136° and 142° meridian East in 1924: that area was discovered in 1840 and named Adélie Land by Capt. J. Dumont d’Urville. Great Britain did not mind, and the Australian sector was not disputed by France.

In 1939, Norway decided to have a piece of the Antarctic pie, declaring that the territory between 20° meridian West and 44° meridian East, namely Queen Maud Land, was its own. In 1940 and 1942, Chile and Argentina entered the dispute and the lands they chose not only partially overlapped, but also invaded Britain’s “Antarctic territories”.

Chile submitted a request for an area between 53° and 90° meridian West; Argentina, for an area between 25° and 74° meridian West. The situation began to heat up.

Furthermore, in 1939, Germany announced the creation of the German Antarctic Sector, namely New Swabia, while Japan also formalised its claims to a substantial area of Antarctic ice.

Again in 1939, for the first time the USSR expressed – as a premise and postulate – that Antarctica belonged to all mankind. After the end of World War II, all legal acts of the Third Reich were abandoned and Japan renounced all its overseas territorial claims under the San Francisco Peace Treaty. According to unofficial Japanese statements, however, the country claims its own technical equipment: according to its own version, the deposits lie so deep that no one except Japan possesses the technology to recover and develop them.

By the middle of the 20th century, disputes over Antarctica became particularly acute: three out of seven countries claiming the lands were unable to divide up the areas by mutual agreement. The situation caused considerable discontent among other States, and hampered scientific research. Hence it came time to implement that idea, the results of which have been outlined above.

In 1998, the Protocol on Environmental Protection was added to the Antarctic Treaty. In 1988, the Convention on the Management of Antarctic Mineral Resources had also be opened for signature, but it did not enter into force due to the refusal of the democratic Australian and French governments to sign it. That Convention, however, enshrined great respect for the environment, which laid the foundations for the Protocol on Environmental Protection. Article 7 of that Protocol prohibits any activity relating to mineral resources in Antarctica other than scientific activity. The duration of the Protocol is set at 50 years, i.e. until 2048.

Most likely, its period of validity will be extended, but we have to be prepared for any development of events. Earth’s resources are inevitably running out and it is much cheaper to extract oil and coal in Antarctica than in space. So an oxymoronically near distant dystopian future awaits us.

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense