The Taliban will seek to run Afghanistan in line with their values and. America will have to stand back and watch.

Drawing lessons from the U.S. involvement in the war in Afghanistan is important not only for determining the ways we may fight in the future, if we must engage in another war in the region (say, dealing with an Iran bent on gaining nukes), but also for shaping our positions in the current negotiations with the Taliban. It turns out that the facts are screamingly different from the prevailing narrative that we are again retreating after a Vietnam-like defeat. The facts show that, far from losing the war in Afghanistan, we won the war easily, with few casualties and costs. The very large number of casualties and $2 trillion squandered resulted largely from our misguided notion that we can turn Afghanistan into a stable, U.S.-like democracy.

The United States went to war in Afghanistan to destroy Al Qaeda and punish the Taliban, which had granted Al Qaeda sanctuary. The war started on October 7, 2001, when the United States began bombing Afghanistan. The number of U.S. troops involved was small. Approximately one thousand U.S. troops participated in this action, along with 110 CIA operatives. The goal was to hit Taliban positions in order to clear the way for the advance of the Northern Alliance, a conglomeration of five Afghan groups, loosely unified around their shared opposition to the Taliban. Their ranks amounted to some fifteen thousand combatants, and they did most of the fighting. On November 9, Northern Alliance forces took Mazar-e-Sharif, precipitating the collapse of the Taliban. On December 9, 2001, merely two months after the start of the campaign, the Taliban regime officially came to an end. According toicasualties.org, the United States suffered a total of eight fatalities during the time span of these operations.

After the fall of the Taliban, the United States stayed in Afghanistan, partly to fight some of the remnants of Al Qaeda, but mainly to turn Afghanistan into a stable democracy, which was deemed necessary to prevent a return of Al Qaeda and which fit into the general American drive to bring liberal regimes to the nations of the world. True, the Taliban did host Al Qaeda, whose operatives were not locals but Saudis and people of other nationalities, because of their cultural tradition to be hospitable, as well as some religious affinity. However, the Taliban never shared Al Qaeda’s goal to attack the United States—the extremist group merely sought to regain control of their own country. Soon, though, the United States treated the Taliban in the same way it treated Al Qaeda—both came to be viewed as insurgent forces against the U.S.-favored democratic Afghan government. However, as shown by the Afghanistan Papers investigation, a comprehensive study by the Washington Post, “Washington foolishly tr[ying] to reinvent Afghanistan in its own image by imposing a centralized democracy and free-market economy on an ancient, tribal society that was unsuited for either.” The effort deepened the very pervasive corruption in Afghanistan. The cultivation of poppies, which was banned under the Taliban, was renewed, turning Afghanistan into the world’s largest exporter of heroin. Elections were rigged. Judges could be bought. Nonetheless, the United States kept insisting, despite high numbers of casualties on both sides and high costs, that it could turn Afghanistan into a stable Western ally. (The developments in Iraq followed a rather similar course.)

In short, the lesson of the war in Afghanistan is that if we must fight again, we can easily defeat the powers in this region—but not engage in successful regime change. The right model of war is illustrated by our 1991 intervention, in which the United States and its allies defeated Iraq easily, drove it out of Kuwait, and thereby reinforced the basic tenet of the international order that no nation can march into another. At the same time, the United States decided not to march into Baghdad and engage in regime change. Similarly, the United States was very successful in stopping the ethnic cleansing in Kosovo—in a short period, with very few casualties—but wisely left the painful nation-building that followed to the UN.

What are the implications of all these findings for the current negotiations with the Taliban? It makes sense to demand that the Taliban promises never to host terrorists again and set up ways to enforce this agreement. However, we should resist calls to continue fighting if the Taliban will not agree to also observe various individual rights and a democratic regime. Otherwise, we will be fighting there for the next sixty years or longer (as one Pentagon maven called for). One must expect that the Taliban will seek to run the country basically in line with their values. Unfortunately, the weak and corrupt regime the United States propped up has not built enough legitimacy to provide much of a counterweight.

Amitai Etzioni is a university professor and professor of international affairs at The George Washington University.

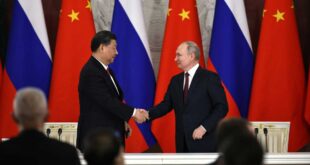

Image: Reuters

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense