Ian Bond

Obama is not an instinctive pro-European. He opposes Brexit because it risks creating more problems for America in Europe. His successor too will want Europe to be a partner, not a passenger, for the US.

No-one believes that US President Barack Obama is coming to London on April 21st to have lunch with The Queen and celebrate her 90th birthday, as the White House claims. Both those who support Brexit and those who want Britain to remain in the EU think that the President is coming to make the case for the UK to vote to stay in the Union. They are correspondingly outraged or delighted by his visit.

There are risks in the visit: some in the eurosceptic camp predict a backlash against foreign interference in domestic affairs. The Conservative former defence secretary, Liam Fox, has long been a eurosceptic, but also staunchly pro-American. He told The Guardian, however, that Obama would be “welcome to his view when the US has an open border with Mexico, a supreme court in Toronto and the US budget set by a pan-American committee.” The mayor of London, Boris Johnson, said that Obama would be “nakedly hypocritical” if he encouraged the UK to remain in the EU. So why is Obama willing to alienate at least some British politicians and voters?

Obama does not have the sentimental attachment to the UK that some of his predecessors have had. Nor is he an instinctive pro-European. That is clear from Jeffrey Goldberg’s analysis of Obama’s foreign policy in The Atlantic: Obama reportedly warned Cameron ahead of the publication of the UK’s National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review in November 2015 that if the UK did not commit itself to meeting the NATO target of spending 2 per cent of GDP on defence, it would no longer be able to claim a ‘special relationship’ with the US. And he comes across as almost contemptuous of European military efforts against Muammar Qadhafi in Libya in 2011, and the failure of the UK and France to plan for the aftermath of the conflict or to follow up their military success. Goldberg quotes Obama as saying that David Cameron was “distracted by a range of other things” after the fall of Qadhafi – perhaps a reference to the growing debate about the EU within the Conservative party.

More than his predecessors, Obama sees America’s allies and partners, in Europe and elsewhere, in terms of how they can contribute to US goals, not what they demand from America. His intervention in the UK’s referendum campaign should be seen in that light. His focus is on how Brexit would affect Europe’s ability to help America tackle international problems.

Since the end of the Cold War, US administrations of both parties have looked to Europe as a net contributor to global security, and to the UK as a bridge between America and the EU. Britain is more activist in its foreign policy than most EU member-states and has helped the member-states to forge a consensus on issues such as EU sanctions against Iran and Europe’s firm response to Russian actions in Ukraine. The UK has also helped keep Washington and Brussels pointing in roughly the same direction on most foreign policy issues (at least since the transatlantic split over the Iraq war in 2003), and on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). The US administration would like the UK to continue to play that role.

The UK renegotiation and the referendum campaign, however, have added to a sense in Washington that the UK is not the ally that it used to be. Many in the American military were unimpressed by the UK’s performance in Afghanistan and Iraq; France, by contrast, has earned respect for its operations in Mali and the Central African Republic, its readiness to accept military risks in pursuit of important goals and its ability to achieve significant results at low cost. The UK’s parliamentary vote against airstrikes on Syria in 2013 also left the impression in the US administration that the UK had become less inclined to use military force at Washington’s behest.

American officials complained privately in the autumn of 2015 that first the Scottish referendum and then the EU referendum were distracting Britain from international problems; and the UK’s renegotiation of its relationship with the EU was distracting the rest of Europe as well. More recently, the Obama administration has been explicit about its worries: in an on-the-record briefing on April 14th, the senior official dealing with Europe in the US National Security Staff, Charles Kupchan, said: “The European Union today faces challenges from populism and other threats to its well-being. And the EU is one of the great accomplishments of the post-World War II era… We would not want to see a Brexit that could potentially damage the European Union and increase the challenges that it faces”.

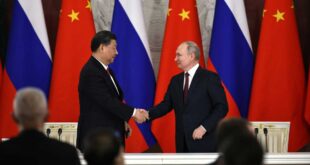

The US itself is having to deal with a number of international challenges: the resurgence of Russia, and the challenge to the international order posed by its invasion of Ukraine and annexation of Crimea; the spread of the Islamic State (Daesh) terrorist movement across the Middle East and North Africa; and above all the rise of China, and the challenge that it poses to stability in East and South East Asia. The US may have by far the world’s mightiest armed forces, but its capabilities are not infinite, and not all of these problems can be dealt with by military force.

All of these challenges bar China are situated on Europe’s doorstep, and Obama wants Europe to do more to solve its own problems. If it is to do so, it needs to be united and focused. At present it is neither. There are disagreements over handling the refugee crisis; a continued economic crisis and no consensus on how to escape from it; and a shortage of strategic thinking on the EU’s goals in its increasingly troubled neighbourhood, let alone on how to achieve them.

The Brexit debate is an unwelcome distraction. The problems that renegotiation was meant to address are mostly either imaginary or home-grown. The British question tied up the European Council meeting in February for many hours before the EU’s leaders struck a deal and returned to the urgent problems facing Europe. Meanwhile, the UK itself has been unable to play its usual leadership role in EU foreign policy, with its political and diplomatic efforts focused first on persuading the rest of the EU to be helpful in the renegotiation, and now turned inwards to make the case for staying in.

If Britain votes on June 23rd to leave the EU, the problems for the US will only get worse. The EU will spend at least two years (and probably much longer) on the unprecedented exercise of unscrambling an egg. After decades of integration, an EU-UK divorce would eat up the energies and efforts of the Commission and the other European institutions, as well as Whitehall. The possibility of Brexit is already encouraging eurosceptics in other member-states to try their luck: Marine Le Pen, of the right-wing populist Front National, has already said that if elected as president of France in 2017 she will call a referendum on French membership of the EU (she also plans to campaign in Britain in favour of Brexit). In countries like Denmark and the Netherlands with strong eurosceptic parties, Brexit could encourage campaigns in favour of referendums on membership. Far from dealing with the EU as an increasingly confident foreign policy actor, the US will find itself trying to manage the fragmentation of one of the building blocks of European stability and prosperity.

All this instability in Europe would be developing as the US itself is in transition to a new administration. Opinion polls suggest that Hillary Clinton will succeed Obama, which at least implies more continuity than if the likely Republican candidate, Donald Trump, wins. Trump is at the extreme end of US views about Europe, suggesting that America can no longer afford to support NATO and defend Europe. But as Secretary of State, it was Clinton who invented the term “pivot to Asia”; it was her Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia, Kurt Campbell, who tried to get the EU and its largest member-states to work with the US in pursuit of common goals in the Pacific region; and the UK was one of the main supporters of that joint approach. Burden-sharing with Europe, whether in terms of defence budgets or political engagement in solving international problems, will still be on the agenda under a Clinton presidency. An EU without the UK, militarily less capable, diplomatically less ambitious and economically destabilised, would be a far less capable partner for America.

Obama has summed up his foreign policy doctrine as “Don’t do stupid shit”. His goal in London is to persuade British voters – both in America’s interest and in Britain’s – that leaving the EU would be ‘stupid shit’.

Ian Bond is director of foreign policy at the Centre for European Reform.

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense