LEONIE ANSEMS DE VRIES, GLENDA GARELLI, and MARTINA TAZZIOLI

The fracturing demands a rethink of the terms usually employed for describing migration movements, such as ‘route’ and ‘border crossing.’ Introduction to a rethink.

In the past few years, transit points have increasingly become the landmarks of transient populations seeking refuge in Europe. From railway stations in European cities, to the ‘jungle’ in Calais; from the brand new ‘hotspot’ onLampedusa island to the Idomeni camp at the Greek-Macedonian border; from squats in Paris to the rocks of the Ventimiglia shoreline, the movements of refugees in transit, as well as the techniques that govern them en route, have taken centre stage in the Mediterranean migration crisis. We see these journeys not just as flight from violence but also as struggles for safety, mobility and recognition.

This article is the first piece of a series in which we report the initial insights gained as part of the research project, ‘Documenting the humanitarian migration crisis in the Mediterranean’, based at Queen Mary University of London. The project studies migration trajectories across Europe from Sicily to the UK to gain a clear picture of the complexity of refugee journeys, the diversity of their situations, and the implications of migration management policies, which are implemented in a diversity of ways across Europe. The policies of finger-printing and refugee hosting are especially significant in this context (as we report in other articles in this series). These insights will help us understand a migration crisis that is too often framed in terms of threat and security.

Transit points

The journeys of refugees tend to enter the public debate either as straightforward routes or punctual instances of border crossings. Yet, by taking the perspective of transit points it becomes clear that to get from A to B for a refugee takes a long time, and presents multiple interruptions, forced stops, decelerated movements, and enduring hardships.

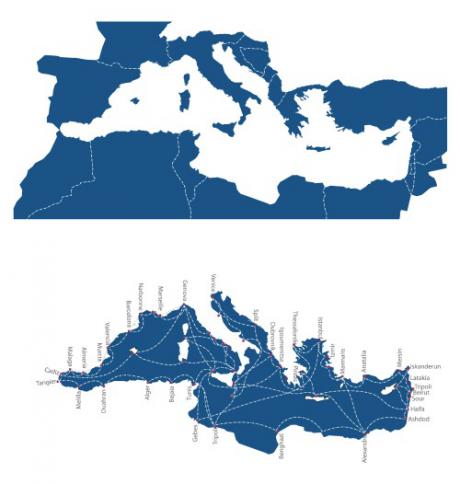

Rather than linear flows from origin to destination, refugee journeys to and across Europe are fractured and rapidly changing trajectories, due to a combination of institutional obstacles (borders, check points, push backs, finger printing, etc.), obstacles in the ‘natural’ environment (sea, mountains, etc.) and local frictions.

This fracturing demands a rethink of the terms usually employed for describing migration movements, such as ‘route’ and ‘border crossing.’ In this series we focus the notion of ‘transit point’ as an alternative perspective.

In addition to highlighting the fractured character of migration journeys, this approach also reveals that the migration crisis in Europe consists of multiple crises: starting with the crises people flee from, through the hardships of fractured journeys, to encounters with a European border regime that is itself in crisis.

For those who survive and reach Europe, the myth of ‘free circulation’ is rapidly exposed. Refugees encounter, for instance, the fenced up eastern borders of Europe; the crisis of Schengen exemplified by the re-introduction and intensification of border checks in France, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden; and, acts of racism and anti-migration protests throughout Europe. Yet, these crises are in some ways countered by the determination of refugees to move, as well as by manifestations of solidarity. We can think, for instance, of the German “Refugees Welcome” initiative, which includes a network of housing and other support; of activists who drive their private cars to Hungary to pick up refugees and drive them to Austria; of the Italian support network for refugees in Ventimiglia on the border with France.

Time and place

What are the transit points refugees encounter? How are refugees accommodated in European and national hosting systems, and what kind of more informal spaces do they inhabit, create and/or appropriate? The migration transit points across Europe can be categorised in a variety of ways. We focus on two: temporality (transient versus permanent sites) and level of institutionalisation (formal versus informal places).

For instance, we look at Lampedusa, a formalised transit point, with respect tothe hotspot system recently inaugurated by the EU; informal yet permanent transit points like the jungle of Calais; and, contingent and improvised stations of passing and residence in Italian and French cities for instance in parks, railway stations and abandoned buildings, which appear and disappear, seemingly without leaving a trace. These last transit points are often highly susceptible to eviction, dependent as they are on the tolerance of local authorities and populations. Often, these spaces are made to disappear as soon as they come to be regarded as an inconvenience, for instance before the onset of winter imposes a duty to offer a warm refuge to any homeless people in a particular city.

Another example is the Lycée ‘Jean-Quarré’ in the 19th arrondissement of Paris, a building that was left empty when a new school building opened next door. The Lycée was occupied by a few hundred refugees at the end of July 2015, some of whom had a history of evictions from transit points, having been forcefully removed from a makeshift camp below the metro tracks of the La Chapelle station.

When police evicted the building in October 2015 it hosted between 700 and 1,000 refugees. Transit points such as these are spaces of concentration of refugees, spaces of struggle and spaces of intense negotiation. In this case, refugees and activists sought to negotiate with the municipality to find a place to stay in the city centre rather than being transferred to remote suburbs, with little access to urban networks of support – to no avail. As illustrated in this example, the contingent and transitory character of these spaces is often an effect of governmental decisions.

The “jungle”

The most prominent – but certainly not the only – case of an informal yet enduring transit point is the Calais “jungle”, which has become a (semi-)permanent border zone. This refugee settlement located on a wasteland just outside of Calais in France hosts around 6,000 refugees who wait for an opportunity to cross the Channel to the UK, stowing away on a truck, car, ferry or train headed for the UK via the port or Eurotunnel. The “jungle” is at once an informal encampment of makeshift shelters; a town under construction, with shops, restaurants and schools; and, a space subject to institutional violence as manifested in the recent destruction of part of the camp.<>

One of the articles in this series will elaborate on the simultaneity of processes of transience and persistence that characterise this transit point. Here, we merely note that whilst both the French and UK governments regard the “jungle” as a problem to get rid of, it is in large part due to the very migration management policies of these governments – e.g. increasingly advanced border controls, fences and technologies – that the “jungle” emerged in the first place, and has become a permanent space of transit and residence.

Summing up

Our project ‘Documenting the humanitarian migration crisis’ follows the trajectories of refugees in their uneven temporality and fragmented nature. Drawing on this research, this open Democracy series will offer an insight into the daily lives and struggles of refugees as well as the governmental practices they confront en route: in the institutional border-zones of Lampedusa (Garelli and Tazzioli) and Palermo (Sciurba); and, in the informal yet securitised border-zone of Calais (Ansems de Vries).

Lampedusa, together with Trapani and Pozzallo in Italy and Lesbos in Greece – these have become experimental grounds for the new hotspot system, marked by the proliferation of identification procedures and strategies for the rapid separation of those who are regarded as eligible for protection from those who are demarcated as not. Across these and other European locations, even the idea of ‘the refugee’ must be called into question. People’s plans and opportunities change as they move across Europe and test their chances for a safe refuge; encounter improvised and established border controls; wait for asylum processing; become subject to detention and/or deportation; or, are illegalised and thereby further removed from the channels of protection.

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense