Giancarlo Elia Valori

Last August the Libyan Investment Authority (LIA) moved its Tripoli’s offices to the now famous Tripoli Tower.

The traditional financial institution of Gaddafi’s regime currently manages approximately 67 billion US dollars, most of which are frozen due to the UN sanctions.

Said sanctions shall be gradually removed and replaced with a system of market controls, as the Libyan economy finds its way.

Right now that, after intimidation and serious and often armed threats, LIA has moved to the safer Tripoli Tower.

However, how was LIA established and, above all, what is it today? The Fund, which has some characteristics typical of the oil countries’ sovereign funds, was created in 2006, just as the EU and US economic and trade sanctions against Gaddafi’s regime were slowly being lifted.

The idea underlying the operation was simple and rational, just like the one that had long pushed Norway to create the Government Pension Fund Global, i.e. using the oil profits to avoid the post-energy crisis in Libya and preserve the living standards of the good times.

Hence investing in its post-oil future using the huge surplus generated by the crude oil sales.

From the beginning, LIA had to manage a portfolio of over 65 billion US dollars, but with three policy lines: firstly, 30 billion dollars to be invested in bonds and hedge funds; secondly, business finance and thirdly, the temporary liquidity secured in the Central Bank of Libya and in the Libyan Foreign Bank.

The funds of those two banks soon acquired a value equal to 60% of all LIA assets.

All the companies having relations with foreign markets, from Libya, fell within the scope of the Libyan Investment Fund.

Currently LIA has over 552 subsidiaries.

Nevertheless, there are no documents proving it with certainty. To date there are not even archives that credibly corroborate the LIA budgets and statistics.

Since 2012 it has not even undergone any auditing activity.

There were and there are no strategies for allocating investments nor a plan. The only criterion followed by the Fund managers – now as in the past – is to invest the maximum sums of money in the shortest lapse of time.

The first serious audit was finally carried out by KPMG in June 2011, in the heat of the battle for the survival of Gaddafi’s regime.

At the time, high-risk derivatives transactions were worth as much as 35% of LIA’s total investments – which was incredible for the other global funds.

According to the most secret but reliable sources, however, in 2009 the losses of the Libyan Fund exceeded 2.4 billion US dollars.

What happened, however, in 2011, after the collapse of Gaddafi’s regime? How did LIA and the Libyan African Investment Portfolio (LAIP) act?

In fact, neither company could carry out any operations.

In 2014 alone, LIA’s losses were at least 721 million US dollars.

Moreover, LAIP still holds in its portfolio the Libyan Arab African Investment Company (LAICO), which manages investments – particularly in the real estate sector – in 19 African countries, with specific related companies in Guinea Bissau, Chad and Liberia.

Furthermore, Oil-Libya still operates as a network manager and extractor in at least 18 African countries.

On top of it, the Libyan Fund still owns RascomStar, a satellite and telephone network connecting much of rural Africa.

Within LAIP there is also FM Capital Partners LTD, another real estate Fund.

Nevertheless, as early as the collapse of Gaddafi’s regime, the internal policy lines of LIA and of the other companies separated: 50% of managers wanted to continue the activity according to the classic rules of the Company’s Management, while the others thought they should mainly follow the new political equilibria within Libya.

The last audit carried out by Deloitte also demonstrated that the over 550 subsidiaries were the real problem of the Fund.

Deloitte also assessed that at least 40% of those companies were completely uneconomic and had to be sold quickly.

In this bunch of lame ducks there were, for example, the eight refineries – one of which managed by Oilinvest in Switzerland – which also paid penalties to the Swiss government for obvious environmental reasons.

Allegedly the refinery in Switzerland stopped its activities in 2017.

The traditional investment line of the Libyan Arab Foreign Investment Company (LAFICO) has always been linked to LIA, which currently has over 160 billion US dollars avaialble, including oil, personal income and old foreign investment of Colonel Gaddafi, once again only partially reported to international authorities.

Moreover, according to the LIA managers of the time, the various companies within the Fund did not communicate one another and hence their strategies overlapped.

And the same held true for the interests of their different political offspring.

Moreover, in 2011 an old independent audit showed that the losses before the sanctions that preceded the uprisings amounted to approximately 3.1 billion US dollars.

Gaddafi’s regime started to collapse – a regime which, according to the international narrative, had allegedly accumulated all the money taken by LIA and its subsidiaries.

Obviously this is not true – exactly as it is not true that the “deficit” in Italy’s public finances before the “Bribesville” scandal was caused only by the greed and voracity of the ruling class.

In the countries where there is a destructive psywar and an offensive economic war, these are now the usual models.

It is not by chance that on December 16, 2011 the UN Security Council lifted the specific sanctions against the Central Bank of Libya and the Libyan Foreign Bank (which is not LAFICO) because they had supported the uprisings against Colonel Gaddafi.

In 2014 LIA initiated legal proceedings against Goldman Sachs, which cost it 1.2 billion US dollars, with a bonus for the intermediary bank of 350 million dollars.

The proceedings ended in 2016 and the British judges decided in favour of Goldman Sachs that was entitled to a compensation amounting to one million US dollars.

There was also another legal action brought against Société Générale, which had started in 2014 and later ended with LIA’s partial defeat.

As to the 2018 national budget, for example, the Central Bank of Libya has envisaged the amount of 42,511 billion dinars, broken down as follows: 24.5 for salaries and wages; 6.5 billion dollars for petrol subsidies and 6.7 billion dollars for “other expenses”.

On average the dinar exchange rate is 1.3 as against the dollar, but it is much lower on the black market.

And public spending is all for subsidies and salaries. Very little is spent for welfare – that was Colonel Gaddafi’s asset for gaining consensus. Social wellbeing can be achieved with good stability of oil prices and revenues, which is certainly not the case now.

Moreover, General Haftar militarily conquered the oil sites of the Libyan “oil crescent” on June 14, 2018, after having held back the attacks of the Petroleum Defence Guards of Ibrahim Jadhran, the commander of the force protecting the oil wells and facilities.

According to General Haftar, the condition for reopening wells, as well as storage and transport sites, was the replacement of the Governor of the Central Bank of Libya, Siddiq al-Kabir, with his candidate, namely Mohammad al-Shukri.

Siddiq al-Kabir stated that the Central Bank of Libya has lost 48 billion dinars over the last 4 years and rejected the appointment – formally made by the Tobruk-based Parliament – of his successor, al-Shukri.

Moreover, Siddiq al-Kabir has also been accused of having pocketed a series of Libyan public funds abroad.

Later General Haftar attacked the Central Bank of Libya in Benghazi to collect funds for the salaries of his soldiers.

Hence the current Libyan financial tension lies in the link between banks and oil revenues – two highly problematic situations, both in al-Serraj’s and in the Benghazi governments, as well as in General Khalifa Haftar’s ranks.

It is certainly no coincidence that the Presidential Council decided to impose a 183% tax on currency transactions with banks.

In addition, taxation was introduced on the goods imported by companies before the current tax reform, which is linked to the reform of the allocation of basic commodities to the Libyan population.

The idea is to stabilize prices and hence make the exchange rate between the dinar and the dollar acceptable, which is another root cause of the economic crisis.

The Libyan citizens often demonstrate in front of bank branches, which are constantly undergoing a liquidity crisis. Prices are out of control and the instability of exchange rates harms also oil transactions, as can be easily imagined.

Nevertheless, even the area controlled by the Tobruk-based Parliament and General Haftar’s Forces is not in a better situation.

In fact, Eastern Libya’s banking authorities have already put their banknotes and coins into circulation, which are already partly used and were printed and minted in Russia.

Pursuant to al-Serraj’s decision of May 2016, said banknotes are accepted in the Tripoli area.

Four billion dinars, with the face of Colonel Gaddafi portrayed on them, and of the same dark colour as copper.

According to the most reliable sources, the reserves of the Central Bank of Libya in Bayda – the city hosting the Central Bank of Eastern Libya – are still substantial: 800 million dinars, 60 million euros and 80 million dollars.

Not bad for an area destroyed by war.

Obviously the simple division into two of the Central Bank – of which only the Tripoli branch is internationally recognized – is the root cause of the terrible Weimar-style devaluation of the Libyan dinar, which, as always happens, they try to patch up with the artificial scarcity of the money in circulation.

As Schumpeter taught us, this does not solve the problem, but shifts it to real goods and services, thus increasing their artificial scarcity and hence their cost.

Meanwhile, the economic situation shows some signs of improvement, considering that the 2017 data and statistics point to total revenues (again only for Tripoli’s government) equal to 22.23 billion dinars, of which 19.2 billion dinars of oil exports; 845 million dinars of taxes; 164 million dinars of customs duties, above all on oil, and 2.1 billion dinars of remaining revenue.

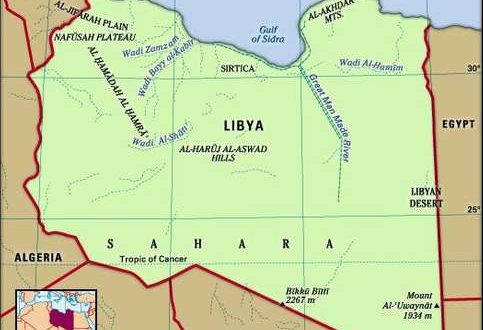

At geopolitical level, however, the tendency to Libya’s partition – which would be a disaster also for oil consumers and, above all, for the Libyan economy, considering that the oil crescent is halfway between the two opposing States – is de facto the prevailing one.

Egypt openly supports General Khalifa Haftar and the tribes helping him.

The Gharyan tribe and many other major ones, totalling 140, now support the Benghazi Government, since at the beginning of clashes, they had often been affiliated to Tripoli and its Government of National Accord.

Tunisia has always tried to reach a very difficult neutral position.

Algeria strongly fears the intrusion of the Emirates’ and Qatar’s Turkish intelligence services into the Libyan economic, oil and political context, but it endeavours above all to limit the Egyptian pressure to the East.

The European powers support General Haftar – with France that, as early as the first inter-Libyan fights, sent him the Brigade Action of its intelligence services. Conversely, Italy is rebuilding its special relationship with al-Serraj’s government – like the one it had with Gaddafi – but with recent openings to General Haftar.

If we want to reach absolute equivalence between the parties, we must avoid doing foreign policy.

Great Britain and the United States tend to quickly withdraw from the Libyan region, thus avoiding to make choices and not tackling the economic and social crisis that could trigger again a war, with the jihad still playing the lion’s share and precisely in the oil crescent.

The United States should not believe that its great oil autonomy, which also pushes it to sell its natural gas abroad, can exempt it from developing a policy putting an end to the unfortunate phase of the “Arab Springs” it had started – of which Gaddafi’s fall is an essential part.

Currently the Libyan production share is around 1% of the total OPEC production.

Everyone is preparing for the significant increase of the oil barrel price, which is expected to reach almost 100 US dollars in the coming months.

If this happened – and it will certainly happen – the Libyan economy could be even safe, but certainly corruption and the overlapping of two financial administrations and two central banks, as well as political insecurity, could still stop Libya’s economic growth.

Hence, for the next international conference scheduled in Palermo for November 12-13, we would need a common economic and financial policy line of all non-Libyan participants to be submitted to both local governments.

Probably General Haftar will not participate – as stated by a member of the Tobruk-based Parliament – but certainly Putin will not participate.

The presence of Mike Pompeo is taken for granted, but probably also the Russian Foreign Minister, Sergey Lavrov, will participate.

Certainly the Italian diplomacy focused only on “Europe” has lost much of the sheen that has characterized it in Africa and the Middle East.

Meanwhile, we could start with a working proposal on the Libyan economy.

For example, a) a European audit for all Libyan state-run companies of both sides.

Later b) the definition of a New Dinar, of which the margin of fluctuation with the dollar, the Euro and the other major international currencies should be established.

Some observers should also be involved, such as China.

Furthermore, an independent authority should be created, which should be accountable to the Libyan governments, but also to the EU, on the public finances of the two Libyan governments.

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense