Hadi Elis

The Kurdish struggle in Turkey has evolved over several decades, marked by complex dynamics and historical context. It is important to examine the socio-political factors that have contributed to the Kurdish people’s fight for self-determination and their grievances against the Turkish state.

The conflict between the Turkish government and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) began in the early 1980s. While the Turkish government initially framed its operations against the PKK as “police operations,” the situation escalated into a low-intensity armed conflict in the mid-1990s. From an international humanitarian law perspective, the conflict can be classified as an armed conflict of a non-international character.

The PKK, as a non-state armed entity, is seen by some as a group engaged in a national liberation war against a racist regime. The Turkish state’s policies have been accused of being discriminatory and racist, falling within the framework of “state terrorism” as understood in terrorism studies.

The Kurdish people’s struggle against the Turkish regime aligns with the principles outlined in Convention 3103, which addresses the legal status of combatants fighting against colonial and alien domination and racist regimes. Additionally, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, adopted by the UN General Assembly, condemns racial discrimination and emphasizes the equal enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms.

The Kurdish people’s claim to self-determination is rooted in their fight against racism and an alien regime. They have endured extreme forms of racism and human rights violations perpetrated by the Turkish state. The evidence of these violations is well-documented, and the Kurdish people argue that they are compelled to rebel against tyranny and oppression, as recognized in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

It is crucial to note that the oppression and tyranny faced by the Kurdish people preceded the establishment of the PKK in 1984. The PKK, through its armed wing initially known as ARGK (Artesa Rizgaria Gel’e Kurdistan; Kurdistan National Liberation Army) and later transformed into HPG (People’s Defense Forces), took up military defense after exhausting political avenues for settlement under the Turkish regime.

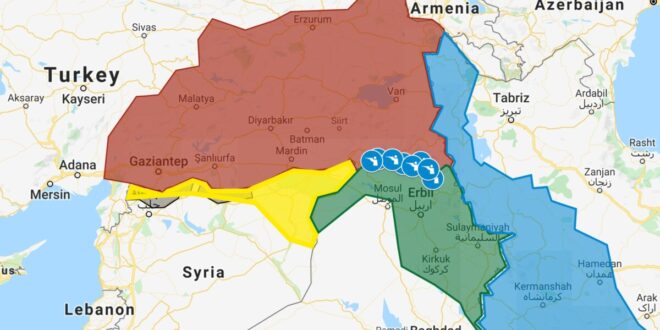

Throughout the Turkey-Kurdish War, the Turkish armed forces have been accused of gross violations of international humanitarian law, human rights law, and crimes against humanity. The applicable law to the non-international armed conflict with the PKK includes the common article of the 1949 Geneva Conventions and the 1977 Additional Protocol II, despite Turkey not being a party to the latter. Turkey’s exercise of effective control over areas and individuals outside its territory, such as military incursions into Iraq, Iran, Syria, and the illegal abduction of Abdullah Ocalan from Kenya, extends the application of international humanitarian law.

In the 21st century, amid the claims of globalization defining human progress, the international community has a responsibility to prevent authoritarian and totalitarian regimes from committing gross human rights violations. In cases where severe human rights violations and humanitarian crises occur, the principle of humanitarian intervention may justify the use of force without seeking the consent of the targeted state.

Respect for human rights and the prevention of gross violations, including genocide, are international obligations of all states. The authorization of the use of force to protect the Libyan people from human rights violations by their own government, as exemplified by UN Resolution 1973, has been seen as evidence of the acceptance of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) principle. This principle could also be applicable to the situation of the Kurds in Turkey.

In conclusion, the Kurdish struggle in Turkey has its roots in persistent racism and patterns of human rights violations committed by the Turkish state. The Kurdish people’s fight for self-determination is driven by the need to combat oppression and tyranny. It is essential for the international community to address the human rights concerns and humanitarian crisis in the region, considering the principle of Responsibility to Protect.

25 years have passed since the NATO Alliance used military force in Kosovo without authorization from the Security Council. This controversial military campaign sparked a debate on whether it marked a turning point in the law regarding humanitarian intervention and a departure from the strict conditions established in the UN Charter for the permissible use of force in international relations.

The debate centered around the emergence of a new doctrine of humanitarian intervention that would justify the use of force to prevent a state from committing or allowing atrocities, particularly when the Security Council is unable to respond due to a veto.

When a state commits an internationally wrongful act that violates human dignity, the right to life, and other human rights, it brings about obligations not only for that state but also for other states as agents of enforcement. These obligations arise from the international community as a whole and involve the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) and humanitarian intervention.

In light of the above, the Turkish state regime has been engaging in gross violations of human rights against the Kurdish people, utilizing extreme violence through its army and police forces. This situation necessitates a humanitarian intervention.

The origins of the Turco-Kurdish war are rooted in racism and discrimination by the Turkish state since its establishment in 1923. The criminalization of the Kurdish language and the renaming of Kurds as “Mountain Turks” as part of a racist denial policy are notable examples.

The Turkish state has systematically blocked legal and political avenues for the Kurdish people, denying them legal and political representation by categorizing them as “non-Turks.”

The only way to counter the assimilation policies and prevent annihilation was through armed resistance for national liberation against the racist regime.

Turkey’s oppression of the Kurds not only violates international law and UN conventions but also its own domestic laws, including the Turkish constitution.

The military coup d’état on September 12, 1980, exacerbated the situation with the extreme militarization of Kurdish regions and strict control over everyday life. Military curfews were imposed, and armed conflict cases were handled by military courts.

The PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) has a political stance on the Kurdish issue, which includes ending the denial of the existence of Kurdish people by the Republic of Turkey and repealing all racist and discriminatory laws. They advocate for Kurdish political representation within the Turkish democracy through the parliamentary system.

Furthermore, the PKK has committed to respecting the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the First Protocol of 1977 regarding the conduct of hostilities and the protection of war victims. They consider these obligations to have the force of law for their own forces and within the areas under their control since January 1995.

Turkey’s Reaction to PKK’s Armed Resistance Struggle

The Turkish government has maintained its policies of denial, assimilation, and oppression in response to the Kurdish struggle.

One approach used by Turkey is psychological warfare, aimed at discrediting the Kurdish struggle and labeling it as “terrorism” against a NATO member and Western ally, rather than recognizing it as a legitimate struggle against the racist regime of the Republic of Turkey.

Turkey has also employed failed counter-terrorism strategies as a means to avoid addressing the root of the problem.

The Turkish government has taken advantage of its relations with the Western world and its membership in NATO while denying the rights of Kurdish people to live as Kurds in peace, democracy, and prosperity.

Illegal “deep state” organizations have been identified within the Turkish military and intelligence services, including a group known as JITEM. These organizations have disguised themselves as PKK fighters, wearing PKK uniforms, to conduct raids on Kurdish villages and commit massacres. The European Court of Human Rights has gathered testimonies and evidence exposing the actions of JITEM and Special Forces.

In April 1990, the Turkish government enacted Decree 413, granting extraordinary powers to a “super-governor” in the OHAL (Military ruled region) in Southeastern Anatolia. These powers included censoring the press, banning publications, confiscating and heavily fining publications that misrepresented the government’s activities, shutting down printing plants, exiling individuals considered harmful to public order, controlling or prohibiting trade union activities, transferring state employees, evacuating villages for security reasons, and preventing legal appeals against these measures. Subsequent revisions to the law, known as Decrees 424 and 425, further expanded the super-governor’s power to exile people from the region.

Political parties that were established to address state oppression against the Kurdish people through legal and parliamentary means, such as HEP, DEP, HADEP, DEHAP, and others, were closed down by the Constitutional Court, blocking their efforts to advance democratization and create a regime that respects human rights.

The Turkish government has been responsible for the evacuation and destruction of close to 4,000 villages, as well as the demolition of homes.

Over 20,000 people have disappeared, and their mothers, known as “Saturday Mothers,” have been tirelessly seeking information about their whereabouts for over 20 years, gathering in front of Galatasaray High School.

Systematic torture has been inflicted on over a million Kurds.

Hundreds of thousands of Kurdish books, music tapes, CDs, and VHS videos have been confiscated, burned, or buried.

The Susurluk incident in 1996 brought to light the connections between the state and the mafia. In this incident, a car accident involved Abdullah Catli, a wanted murderer and drug trafficker, Huseyin Kocadag, a former Deputy Head of the Istanbul Police Department, and Sedat Bucak, an MP from DYP and the leader of government-paid militias known as village guards. The car contained a fake passport, official diplomatic credentials, weapon permits, drugs, and a large sum of money.

The Susurluk incident provided solid official evidence linking the activities of the Gendarmerie Intelligence and anti-terror organization (JITEM) and the Presidency of Police Special Operations Department. It also implicated members of the National Intelligence Agency (MIT) and the RP-DYP coalition government, including then Minister of Internal Affairs Mehmet Agar.

In 2005, a bookstore in Semdinli, a city in the Kurdish regions of Turkey, was bombed. A PKK informant and two non-commissioned officers in charge of JITEM were caught red-handed. The existence of JITEM, despite denial, has been confirmed through various pieces of evidence, such as certificates of appreciation, government salary rolls, investigation committee reports, and confessions of those who worked for the organization.

On December 28th, 2011, Turkish Army warplanes bombed and killed 34 Kurdish civilians, the youngest being 12 years old, from two villages in the Kurdish township of Uludere. This incident is known as the Uludere Massacre. To date, no one responsible from the government and army has faced justice for this tragedy.

The PKK has made several attempts at peace offers, cease-fires, and negotiations. The first internationally publicized cease-fire and call for peace occurred on March 17, 1993. The PKK sent letters to Western governments, including a request for third-party involvement, with one proposal suggesting the engagement of US President Bill Clinton. This cease-fire lasted until late May 1993.

Subsequent cease-fire and peace offer periods took place from December 10, 1995, to August 1996; September 1, 1998, to June 2004; April 5, 2005, to late May 2005; October 1, 2006, to November 2006; and March 1, 2012 (with re-announcements on March 21, 2013, March 21, 2014, and March 21, 2015). Following the February 10, 2023 earthquake in Turkey’s Kurdish regions, the PKK declared a unilateral ceasefire, which ended on June 14, 2023, without a response from Turkey.

The PKK is open to the involvement of any Western country as a third party in the peace process and has publicly expressed this willingness. They have specifically suggested the United States as a third party for confidence-building measures and monitoring the process. Despite the PKK being listed as a “terrorist” organization by the US and other Western countries, the PKK does not object to their involvement in the peace process on Turkey’s behalf.

Turkey, on the other hand, has rejected the United States and any other Western country as a third party, regardless of their NATO membership, mutually beneficial trade, social and political relations with Turkey, and favorable relations with Turkey. Turkey is aware that the involvement of Western states would necessitate accepting responsibility for war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by its army and law enforcement officials through investigations conducted by a Truth and Reconciliation Committee.

PKK’s position against the regime of the Syrian Arab Republic and Jihadi terrorism, including ISIS: (8)

The regime of the Syrian Arab Republic, commonly known as the Assad regime, opposes the ethnic and democratic rights of the Kurdish people, which are recognized by the UN Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The Syrian opposition coalition, including the Syrian National Council and the Free Syrian Army, is under the control of the Republic of Turkey. As a result, Kurdish participation in the Friends of Syria conferences has been opposed, and Kurds have not been allowed to participate thus far.

The PKK has actively supported Syrian Kurds in organizing themselves politically and militarily to fight for their rights. They have fought against both the Assad regime and Jihadi terrorist organizations, with a particular focus on combating ISIS.

The PKK also engages in fighting against ISIS in Iraq, particularly in the Shingal region, where they aim to protect the Yazidi community.

Turkey’s position regarding the Assad regime, Kurds in Syria, Jihadi terrorism, and ISIS is as follows:

This explanation provides a brief overview of the situation and its connection to Turkey’s current stance and policies in the war against global Jihadi terrorism, specifically ISIS/DAESH.

Turkey desires the removal of the Assad regime from power, although the exact reasons for this stance have not been publicly declared. There are accusations that the Assad regime, like Turkey, violates human rights conventions.

Turkey sponsors the activities of the Syrian National Coalition and the Free Syrian Army against the Assad regime. However, it is important to note that Turkey’s support extends to actions against the Kurdish people in Syria as well.

Turkey has been criticized for exploiting its ties with Western countries, especially the United States and NATO members, to further its objective of removing the Assad regime. This has involved providing financing and training to various opposition groups, including those associated with Al Qaeda and ISIS. It has been reported that some of the individuals trained in Turkish “Train and Equip” camps later joined ISIS, while others joined different factions.

Turkey sees an opportunity with ISIS to weaken the resolve of the Syrian Kurdish people to the point where they would accept Turkey as a guarantor state. This includes proposing a no-fly zone to exert control over the entire Turkish-Syrian border, against the will of the Kurdish people.

ISIS attacks on the PKK have been used as a tool by Turkey to weaken the PKK and bolster Turkey’s position in demanding conditions of peace from the PKK.

However, there has been increasing international attention to Turkey’s alleged sponsorship and support for ISIS, ranging from intelligence sharing to providing medical treatment to ISIS fighters. These actions have led some Western countries to view Turkey as a non-ally state involved in anti-Western, anti-Christian, and anti-Jewish activities for some time.

Notes:

The information provided is a quotation from the Rand Corporation’s book “Occupying Iraq: A History of Coalition Provisional Authority” published in 2009. The quotation highlights the actions of Turkish forces in Iraq and the concerns raised by Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) officials regarding the deployment of Turkish troops and their interactions with the PKK.

According to the book, there were discussions between the Turkish government and the CPA regarding the deployment of Turkish troops to Iraq, particularly in Salahaddin Province, in October. However, this proposal faced substantial opposition from the Kurds, with Massoud Barzani threatening to resign. CPA officials expressed concerns that such a deployment would be counterproductive and could lead to increased interference from Syria and Iran. It was also noted that some Turkish forces had engaged in actions such as wearing U.S. Army uniforms during ambushes on PKK units, possibly to provoke attacks on Coalition Forces.

CPA assessments indicated that there was ambivalence among Kurdish groups in effectively dealing with the PKK and KADEK (an earlier name for the PKK). U.S. military forces encountered Turkish roadblocks inside Iraq aimed at intercepting PKK movements, and there were tense standoffs between Turkish and coalition forces. Some CPA officials believed that the PKK was a terrorist organization but argued against using U.S. and Iraqi military forces to target them.

The book further states that CPA officials considered prioritizing relations with Turkey over targeting the PKK in Iraq to be a mistake. The U.S. military, represented by CJTF-7, opposed the option of targeting PKK forces, citing the need for a significant deployment of troops to carry out such operations. Instead, they advocated for increasing pressure on Kurdish leaders.

References:

- http://ijlljs.in/conflicts-not-of-an-international-character-and-the-applicable-law/

- https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/1969/03/19690312%2008-49%20AM/Ch_IV_2p.pdf

3) Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to

the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts (Protocol II)

Geneva, 8 June 1977 as Massoud Barzani and Jalal Talabani to eliminate PKK safe havens in Iraq’

4) (17 March 2011; Statement on Libya)

5) (https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/draft_articles/9_6_2001.pdf

6) The Overlord State: Turkish Policy and the Kurdish Issue

Philip Robins

International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-)

Vol. 69, No. 4 (Oct., 1993), pp. 657-676 (20 pages)

7) https://merip.org/2018/12/the-failed-resolution-process-and-the-transformation-of-kurdish-politics/

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense