Aakarshan Singh

A Direct Energy Weapon or DEW is weaponry that uses highly focused energy, such as lasers, microwaves, or particle beams, to demolish, harm, impede or decapitate its target. DEW is a long-ranged weapon that damages its targets with highly focused energy. Lasers, microwaves, particle beams, and other similar weapons are a few contemporary examples of the same.

Historically speaking, Archimedes is said to have used mirrors to direct sunlight to destroy warships during the Roman Empire’s campaign against his hometown of Syracuse, according to tradition. Since then, many historians have questioned the reality of such a claim.

In World War II, the German Army created weapons such as the sonic cannon, which caused lethal vibrations in the human body, causing nausea, vertigo, and other symptoms. Experiments employing X-rays as a base were also carried out to pre-ionize ignition in aircraft engines and, therefore, serve as anti-aircraft weapons. The CIA alleged that the Soviet Army employed laser-based weaponry against the Chinese during numerous Sino-Soviet conflicts throughout the Cold War.

Several governments in the Asia-Pacific area are caught up in the worldwide race to build hypersonic and directed-energy weapons, with several big powers developing or publicly announcing their ambitions. DEWs are new cutting-edge military technologies that have yet to be officially deployed by any military power but are expected to be important in future combat.

China and Russia have created unparalleled arsenals of precision-guided missiles and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to overwhelm India’s military defences, much like Russia is doing in Ukraine right now. Because of the magnitude of these threats, conventional kinetic systems such as Patriot missile batteries will be unable to protect US personnel in harm’s way. With the intent to defeat these threats, it will be necessary to combine non-kinetic, directed-energy devices such as high-energy lasers with kinetic defences.

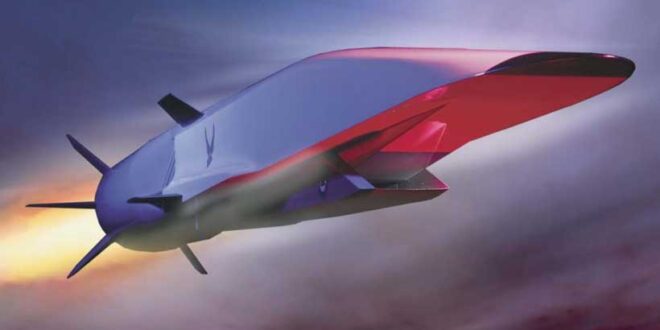

China, predictably, is one of the countries concentrating its efforts in both areas. It is primarily regarded as the market leader in hypersonic weaponry, having previously deployed hypersonic armaments in the shape of the DF-17 hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV).

In late 2019, the DF-17 HGV made its first public appearance at a military parade in Beijing, China’s capital. In its first stage, the weapon appears to use a typical ballistic missile booster to accelerate a glide craft, which is then used to strike an objective after re-entry. At a parade, the DF-17s were installed on a five-axle motorized transporter-erector-launcher. As a result, the unit, like much of the People’s Liberation Army’s ballistic missile armament, is road-mobile, making its use feasible and lethal to the strategic points of its opponents.

The development of DEWs is viewed as especially crucial in India’s deteriorating security situation, particularly its ties with China. According to Indian security experts, as technology advances in India’s neighbourhood, the country may become exposed. They also suggest that India look into the prospect of building combat capabilities in this area. Given the escalating security dynamics in the Indo-Pacific and beyond, many major nations, including India, are expected to step up their efforts to acquire these weapons.

The recent military conflict in eastern Ladakh reminds us of China’s threats to India. Beijing’s expanding military might, including capabilities in space, cyber, and electronic warfare, can significantly threaten its opponents, including India. DEW technologies are also being developed in China. As a result, India is indeed undoubtedly building its own DEWs. “DEWs are tremendously crucial today,” Dr G. Satheesh Reddy, the head of the DRDO, remarked during the 12th Air Chief Marshal L.M. Katre memorial lecture in August 2021. “The rest of the globe is pursuing them. We’re conducting many experiments in the country as well.” he further concluded by briefly showing light on India’s emphasis on the DEWs. Later in December 2021, India’s Defence Research and Development Organization (DRDO) also announced intentions to build directed energy weapons (DEWs) based on high-energy lasers and microwaves.

Further solidifying these claims, the Ministry of Defence launched its second edition of India’s “Technology Perspective and Capability Roadmap” in 2018, showcasing 200 technologies and concepts slated for introduction into the armed services in the mid-2020s. A “Tactical High Energy Laser System” for the Army and Air Force was among the ventures that business was encouraged to adopt.

The ministry envisaged a laser weapon system mounted on high-mobility vehicles that could “cause physical damage/destruction to [electronic warfare] systems, communications networks, quasi communication systems/radars and their antennae.” The armament should ultimately have a baseline range of 20 kilometres, target-locking technology, and the potential to operate as anti-satellite weaponry from both ground and air stations.

In line with the same, India has established a linear electron accelerator system dubbed KALI, or the “kilo ampere linear injector,” for neutralizing long-range missiles. KALI is presumed to quickly dissipate impactful pulses of Relativistic Electron Beams (REB) that can destroy communications components on-board once a missile launch is spotted. Together the DRDO and the BARC worked to create KALI (BARC). Dr R. Chidambaram, the then-Director of BARC, recommended it in 1985. According to reports, construction on the project began in 1989. A high power pulse particle throttle KALI-5000 has been operational with an energy of 650 keV and an electron beam power of 40 GW, the BARC head declared at a BARC Foundation Day address in 2004.

Furthermore, tactically speaking of what is more available as disclosed and non-confidential knowledge in public portals, as per the Congressional report, in a component of its Hypersonic Technology Demonstrator Vehicle project, India grows an indigenous, dual-capable (conventional and nuclear) hypersonic missile system. It has experimentally validated a Mach 6 scramjet in June 2019 and September 2020. “India has about 12 hypersonic wind tunnels that can test speeds up to Mach 13,” says the report.

Later in 2021, India finally joined the elite nations that have successfully tested the High-Speed Technology Demonstrator Vehicle (HSTDV) using an indigenously produced propulsion system. The successful test represented an essential step forward in establishing hypersonic delivery systems, including constructing a carrier vehicle for cruise missiles and the low-cost launch of satellite systems.

The DRDO is also thought to be making progress on a hypersonic anti-ship missile identified as the BrahMos-II. According to a research, hypersonic scramjet technology is projected to achieve speeds twice as fast as the BrahMos-1, thus exceeding Mach 6.

India undertook two significant missile launches in the latter months of 2021. The Shaurya hypersonic armament launch, which took place in October, was the first. The Agni-P missile test, which took place on Christmas Night, was the second. Both missile tests show that India is on track to develop a more advanced nuclear arsenal with a broader range of propulsion systems. These achievements have sparked a flurry of reactions, ranging from delight at the improved preparedness of India’s arsenal to dire predictions about what these missile developments could mean for geopolitical stability, mainly between India, China and Pakistan.

India’s missile arsenal is improving to dissuade and deter the Army of the People’s Republic of China. India’s competencies at the time are much inferior to those of the latter. Beijing has deployed its Dong-Feng (DF)-26 IRBMs in Western China’s Xinjiang province. China’s DF-17 HGV, with an operative ballpark range of 1,800-2,500km, is a significant threat. Beijing is reported to have been operating this since at least 2019, which is also a retaliation to India’s Shaurya hypersonic armament. Due to its limited geography, Pakistan is especially susceptible to strategic interception compared to China’s geographic and strategic depth. In any case, Beijing’s submarine-based nuclear-weapons provide it with a near-invulnerable second-strike capability, complicating India’s counter-force operations versus the Chinese nuclear targets. As a result, India’s hypersonic arsenal, Agni SRBM, and IRBM warheads maintain strategic deterrence and improve its position in South Asia’s geopolitical equilibrium.

DEWs and hypersonic missile systems, in my perspective, should indeed be considered as one component of a more considerable global military technological evolution. Directed-energy weapons will redefine how objectives are captured and attacked in years to come, much as electronic technology has progressed the speed and accuracy of the flow of information. Once the technological impediments outlined above are resolved, the future of this technology could have near-endless potential when it comes to engaging aerial targets like missiles or drones.

The DRDO’s objective and budgetary allocations primarily aim to establish and subsequently operate DEWs that are limited to terrestrial assignments. As a result, it’s possible that India won’t be able to produce the whole array of DEWs. Despite their current technological limitations, the DRDO and the administration will need to recognize which direct energy weapons are sustainable in the long run.

The Chinese are quickly developing and fielding DEWs for attacking and defending purposes. India will not be able to rely solely on defensive qualities to secure and safeguard its troops and equipment; it will also require aggressive DEW capacities, which may be minor but would require intensive and considerable attention.

Many specialists in the industry believe that directed-energy weapons will unravel new forms of lethal and nonlethal engagements in the long term. This, although, would entirely be determined by what is defined as “appropriate.” Despite decades of research into the practical applications of Direct Energy Weapons, they are still thought to be at the experimental stage, even though a few prototypes have been proclaimed to be functional by certain nations.

While the absence of a functional hypersonic missile defence system makes such capabilities appealing, research shows significant hurdles to overcome, such as the propulsion system and the intense heat generated by these weapon systems. G Satheesh Reddy, the DRDO’s chief, had stated that realising a comprehensive weapons system working for some advantage would take approximately four to five years.

While it is an apparent common understanding that the Indian ballistic system and hypersonic missile armaments are present in numbers of strength, there needs to be a constant upscaling to keep up with the ever-evolving warfare strategies and armament systems.

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense