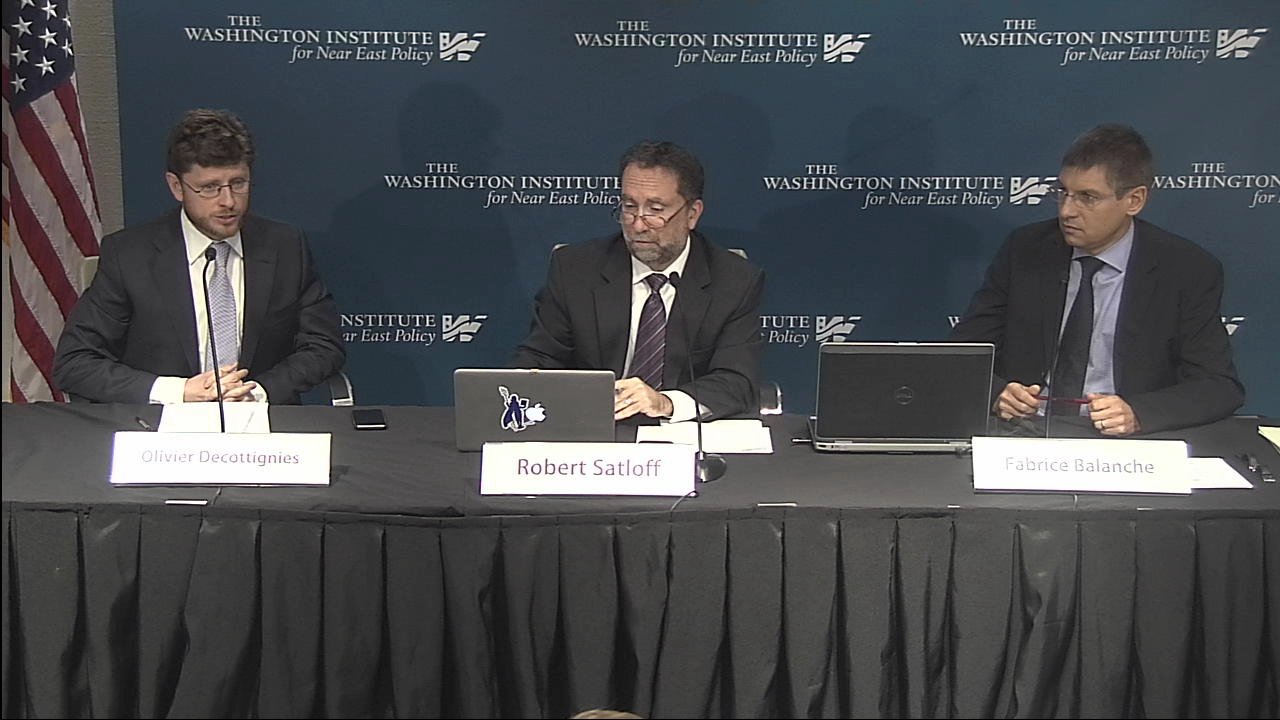

On November 23, Gilles Kepel, Fabrice Balanche, and Olivier Decottignies addressed a Policy Forum at The Washington Institute. Kepel is a professor at the Institute of Political Studies, Paris (Sciences Po), and coauthor of the forthcoming book “Terror in France: The Origin of the French Jihad,” to be published in January. Balanche is an associate professor and research director at the University of Lyon 2 and a visiting fellow at the Institute. Decottignies is a diplomat-in-residence at the Institute and former second counselor at the French embassy in Tehran. The following is a rapporteur’s summary of their remarks.

GILLES KEPEL

In France, both of the terrorist strikes that bookended 2015 — the Charlie Hebdo shooting in January, and this month’s coordinated attacks — belong to the same strategy detailed by radical jihadist ideologue Abu Musab al-Suri in his 2005 book The Call for Global Islamic Resistance. In Suri’s view, Osama bin Laden’s decision to directly attack the United States was a hubris-fueled misstep that incited America to destroy al-Qaeda. He believes that Europe is a more appropriate target not only because it is much weaker than the United States, but also because of its growing Muslim populations. Suri aims to exploit these communities — many of whom are poorly integrated and feel disenfranchised — in order to foment a European civil war between radicalized Muslims and non-Muslims, with the ultimate goal of establishing the caliphate on the continent. To reach this goal, jihadists seek to divide European societies through terrorist tactics while taking advantage of changing demographics in which native populations are declining while Muslim immigrant communities swell. Fearing these demographic consequences, some voters have begun to support far-right political parties such as the National Front, which pollsters are projecting will notch a landslide victory in next month’s French regional elections.

Tactically, however, the January and November attacks differ significantly. The Charlie Hebdo shooting targeted what jihadists consider “enemies of Allah” (e.g., cartoonists, apostates, Jews), but the latest attack indiscriminately targeted the younger Parisian demographic. It was not well organized, however — the plotters were aiming for a higher death toll. For example, the attackers with suicide vests were not able to enter the stadium to target any of the 80,000 people therein, including President Francois Hollande.

While the perpetrators succeeded in terrorizing their enemy, the operation was not an effective strategy for galvanizing sympathizers. Since last week, there has been little expression of solidarity for Daesh outside its core group of Francophone supporters. In fact, the attack may alienate these supporters and herald a strategic defeat in a manner similar to al-Qaeda’s diminution after 9/11, when the international community honed its sights on the organization. Other countries currently involved in the Daesh theater, including Russia, Turkey, and the Gulf states, might finally experience a confluence of interests and identify the group as their most immediate enemy.

FABRICE BALANCHE

Although President Hollande asked Russian leader Vladimir Putin to focus his Syria strikes on Daesh, Moscow is more likely to increase attacks on other rebel groups if it sees that they are threatening the Assad regime. Bashar al-Assad is the Kremlin’s last Arab ally, and this relationship helps secure Russian military bases on the Mediterranean coast. The Syria intervention also gives Russia leverage over Europe by fueling terrorism and refugee flows, both of which are widening political cracks across the EU. Many in Europe doubt the wisdom of any strategy designed to force Assad’s departure, seeing him as a necessary (albeit odious) ally against Daesh. In the end, European governments have been unwilling to publicly revise their policy, instead backing Russia in a way that effectively reinforces the Assad regime.

Russia can also gain strategically from the Syrian Kurdish nation-building effort. The Kurds need outside support, and Western help is limited due to a multitude of conflicting regional objectives. Russia can assist their campaigns in northern Syria, particularly around Jarabulus, and the Kurds prefer this territory over the Daesh capital of Raqqa. Kurdish control in the north would also make it easier for Russia and Assad to target other rebel groups. While Assad wants to regain this territory himself, Kurdish control is an acceptable outcome if it helps him achieve more urgent goals.

Indeed, Assad intends to do everything possible to stay in power — his counterinsurgency approach aims not to win hearts and minds, but to crush the opposition. He often highlights how Syria experienced thirty years of peace after his father Hafez killed thirty thousand people in Hama. Today, Assad’s forces continue to strike moderate opposition groups more than Daesh, which hampers Western efforts to identify a viable alternative to his regime. While Assad did not create Daesh, he accelerated the radicalizing forces that fuel the group, and the West’s dilatory approach to the conflict also played a role in creating the current dilemma: having to choose between Assad and Daesh.

Daesh will not be defeated quickly. The coalition has yet to seize significant amounts of the group’s territory, and Daesh operatives retain the ability to strike abroad in places such as Paris and Beirut. The territory around Aleppo is particularly strategic as it facilitates transit between Syria and Europe. Russia will expel Daesh from this area only if the Syrian army or Kurdish forces can occupy it.

While this is a unique moment in the conflict, President Hollande is unlikely to suggest a profoundly different course of action for coalition forces in Syria during his November 24 meeting with President Obama, apart from redoubling their coordination efforts. As for Russia, if France makes concessions on Crimea, Moscow might show more flexibility in Syria, but Iran would not agree to this. For the time being, then, Moscow and Tehran are unified in their goal to strengthen Assad.

OLIVIER DECOTTIGNIES

France is increasing military operations against Daesh, with the aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle arriving in the Eastern Mediterranean on November 22 to target the group’s key infrastructure in Mosul and Raqqa. Airstrikes alone are insufficient, however; ground troops are needed as well, though not necessarily French forces. In a recent interview, Defense Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian highlighted the liberation of the Sinjar Mountains after a combined effort between Kurdish forces and coalition airstrikes. Similarly, President Hollande’s address to parliament emphasized the need for more support of anti-Daesh forces on the ground.

Daesh may see Europe as the soft underbelly of the West, but France is not the soft underbelly of Europe in defense matters. France has been involved in military efforts against Daesh and other jihadists in Iraq, Syria, and Mali, conducted ongoing stabilization operations in the Central African Republic, and generally served as the EU’s forward line of defense against extremism. Various governments have given encouraging signs of support for these efforts, including Britain providing operational support from its Akrotiri base in Cyprus and Germany possibly deploying troops to Mali. Other issues remain unresolved, however; the British Parliament has yet to approve strikes in Syria, the German press is debating whether the current conflict can be defined as a war, and the recent terrorist attack in Mali might dampen the EU’s response.

France has also chosen not to turn to NATO, instead invoking an EU collective defense clause. The rationale for this decision lies in the French assessment of Daesh as a threat to all of Europe — after all, the Paris attacks were conducted through an elaborate network spanning several EU countries, notably Belgium. France is now demanding measures to secure Europe’s external borders, share passenger data, and institute equitable burden-sharing in other arenas to counter the threat.

This foreign policy reaction fits within the traditional French paradigm: namely, active diplomacy with traditional partners and the UN, a lean but muscular military capability, a will to fight, and a dedication to French and European security. President Hollande’s stated goal is the creation of a large international coalition against Daesh, including Moscow. President Obama’s strong response this weekend regarding the need to defeat Daesh was encouraging, and Hollande’s visit to the United States is part of a series of meetings with the leaders of Britain, Germany, and Russia.

Because a majority of the terrorists were born and raised in France, there is a large domestic component to this challenge as well, and President Hollande devoted most of his parliamentary address to homeland security measures and the need for national unity in the current circumstances. French foreign policy is now playing a strong role in domestic politics; likewise, some aspects of the domestic fight against Daesh have implications for foreign policy matters such as fighting weapons trafficking, countering radical ideology, and curbing terrorism financing.

This summary was prepared by Patrick Schmidt.

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense

Geostrategic Media Political Commentary, Analysis, Security, Defense